The highly anticipated 3rd Edition of the Delhi Arbitration Weekend (DAW 2025) kicked off with a distinguished inaugural session organized by the Delhi International Arbitration Centre (DIAC) at the Additional Building Complex, Supreme Court of India on 18-09-2025.

The event was honored by the presence of esteemed dignitaries, including:

- Justice BR Gavai, Chief Justice of India, who graced the occasion as the Chief Guest.

- Justice Devendra Kumar Upadhyaya, Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court.

-

Justice Stephen Gageler AC, Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia.

The inaugural session set the tone for what promises to be an enriching and impactful series of discussions and exchanges on the future of arbitration. The distinguished speakers and attendees engaged in insightful deliberations, reflecting the growing significance of India in the global arbitration landscape.

Also read : Live from DAW 2025: Inaugural Session of the 3rd Edition of Delhi Arbitration Weekend

Day 1 of the DAW 2025 featured a series of engaging and insightful sessions, bringing together leading voices from the global arbitration community. Each session provided valuable perspectives on the evolving landscape of international arbitration, addressing both practical considerations and emerging trends. The robust participation and high-quality discourse on Day 1 set a strong foundation for the remainder of the event.

Session 1 | Arbitration 2.0: Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Other Technologies to Enhance the Efficiency of Arbitration

Hosted by the Supreme Court of India, the High Court of Delhi, and the Delhi International Arbitration Centre (DIAC)

The first session of Day 2, titled “Arbitration 2.0: Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Other Technologies to Enhance the Efficiency of Arbitration,” explored the transformative potential of emerging technologies in reshaping the arbitration landscape.

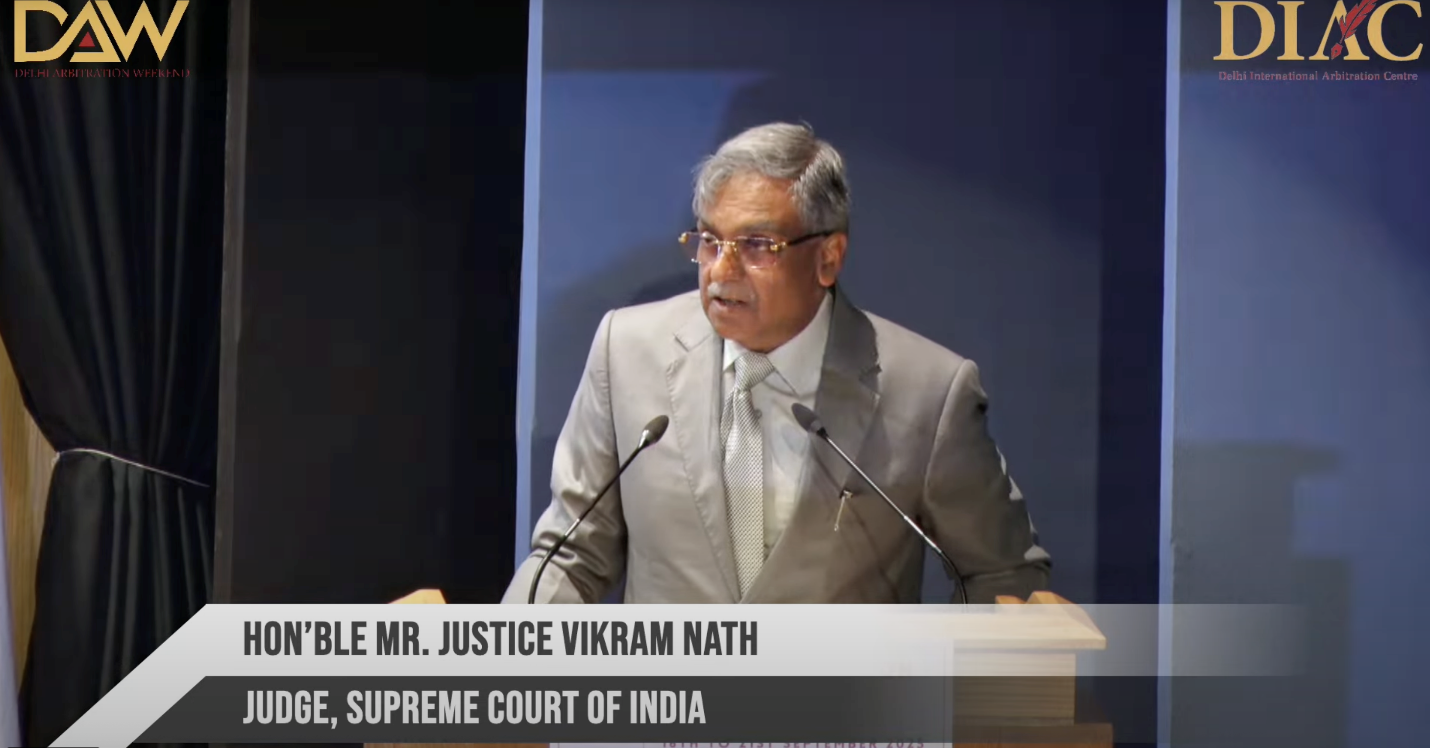

The session was chaired by Justice Vikram Nath, Judge, Supreme Court of India, who opened the discussion by highlighting the judiciary’s evolving engagement with technological advancements.

An esteemed panel of speakers contributed valuable perspectives:

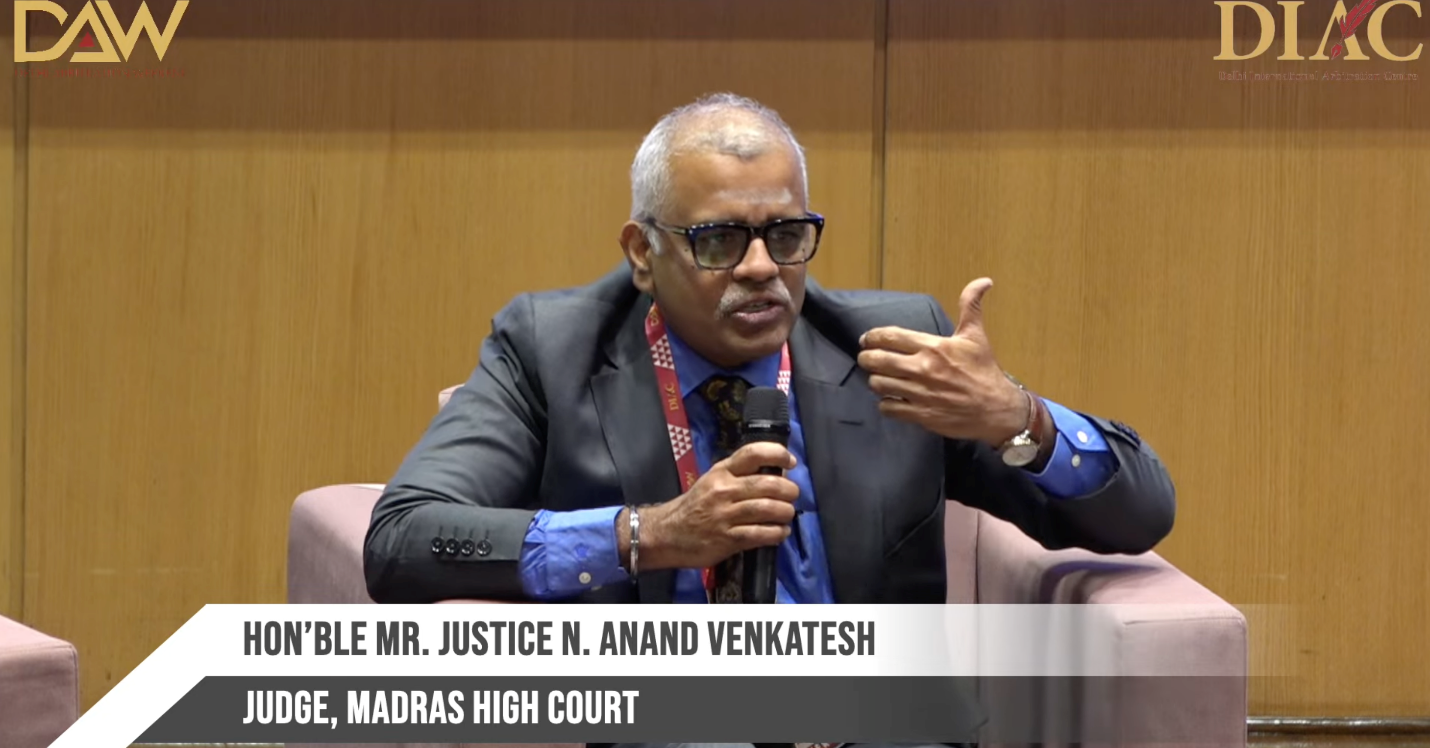

- Justice N. Anand Venkatesh, Judge, Madras High Court

- Tushar Mehta, Learned Solicitor General of India

- Mark Dempsey SC, Independent Arbitrator

-

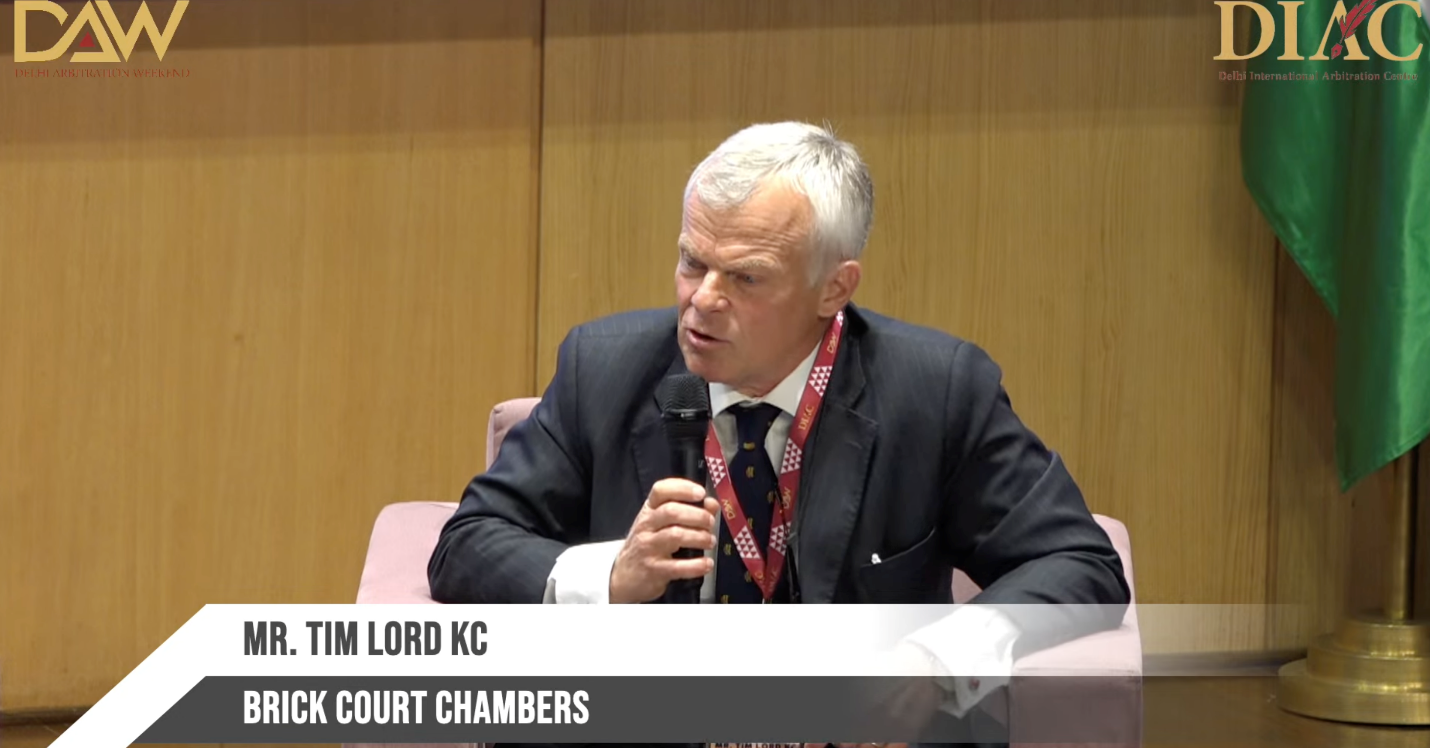

Tim Lord KC, Brick Court Chambers

The panel delved into the implications of AI and digital tools in streamlining arbitral procedures, reducing costs, and improving accessibility. They also addressed the ethical, legal, and practical challenges that accompany this digital shift, setting the tone for future-ready arbitration frameworks.

Opening Remarks by Justice Vikram Nath

Justice Vikram Nath warmly welcomed all dignitaries, panelists, and delegates, acknowledging the presence of judges from across India, including Gujarat, Allahabad, and Madras High Courts, as well as senior advocates, arbitrators, and international guests.

He set the stage by reflecting on the rapid pace at which technology is transforming professional sectors globally. Drawing on a compelling example from Stanford University, he described a recent experiment where AI systems operated as virtual researchers, debating hypotheses, designing experiments, and developing drug prototypes with minimal human input. While cautioning that law is not a laboratory science, he noted that similar tools could significantly enhance arbitration’s effectiveness, particularly in areas such as document review, data analysis, and case prediction.

Justice Nath emphasised that arbitration, from its inception, was envisioned as a faster, more flexible alternative to traditional litigation. As the legal system evolves, he stressed that arbitration must also adapt, embracing Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, and other technological innovations.

“AI can be a powerful assistant, helping humans work faster and more efficiently. It can be a powerful collaborator, accelerating human work in ways we are only beginning to understand.”

He illustrated the global momentum by highlighting platforms such as SIAC’s Gateway system and the Silicon Valley Arbitration & Mediation Center’s guidelines on responsible AI use. Closer to home, he shared advancements being piloted by the Indian judiciary, such as:

- Real-time AI-powered transcription in Supreme Court proceedings

- Translation of judgments into 18 Indian languages using machine learning

-

SUPACE (Supreme Court Portal for Assistance in Court Efficiency) — an AI tool that analyses case facts, identifies precedents, and aids legal research

“If arbitration was designed to save time, then AI has the potential to redefine what time even means, in dispute resolution.”

Justice Nath also touched upon crucial legal and ethical questions, including data security, transparency in AI usage, and the need for judicial training. He cautioned against over-reliance on AI, citing an ongoing case in California where a party challenged an arbitral award, alleging that the arbitrator used AI to draft parts of the decision.

“I often say that as exciting as AI and technology are, we must remember that justice is at its core, human. It requires what I call a heartbeat. Machines can sift through documents, highlight patterns, and even predict outcomes, but they cannot weigh fairness against experience. They cannot temper strict legal logic with human empathy.”

He concluded his remarks with a strong message on embracing technological tools responsibly, leveraging their potential while preserving the human values that lie at the heart of justice.

“The future of arbitration is being written today, let us ensure we write it well.”

Insights from Panel Discussion

Following his opening address, Justice Nath initiated the panel discussion by posing the first question to Justice N. Anand Venkatesh:

“Apart from Generative AI, what are the other technologies that are dominant within the legal fraternity at large, and arbitration in particular? How do you understand the difference between Generative AI and other technologies in a way that they affect and assist with the various tasks involved in the dispensation of legal duties, from the perspective of litigants, counsels, and adjudicatory bodies alike?”

Justice N. Anand Venkatesh provided an insightful perspective on the technological evolution of arbitration and the transformative potential of AI in the legal domain.

He began by tracing the journey of arbitration from paper-intensive proceedings to digitalised case management systems, which significantly enhanced the efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and accessibility of arbitration. He highlighted several digital tools that have become integral to legal practice today.

Justice Venkatesh then turned to the distinction between conventional digital technologies and Artificial Intelligence, offering relatable analogies to illustrate his point. For instance:

“When I walk up to a coffee machine and press a button for cappuccino, it simply performs the task — that’s technology. But when the machine senses my presence and prepares the coffee, I usually prefer at that time of day — that’s AI.”

Similarly, he explained how platforms like YouTube suggest music based on user behavior and preferences, illustrating how AI learns patterns, predicts choices, and begins to “read who we are.”

Justice Venkatesh then turned to the distinction between conventional digital technologies and Artificial Intelligence, offering relatable analogies to illustrate his point.

He emphasised that AI marks a shift from passive execution to active participation, transitioning from a tool that follows instructions to one that anticipates needs, analyses data, and in some cases, makes decisions. This paradigm shift, he noted, holds immense implications for arbitration.

AI in arbitration, he observed, is already making inroads in several critical functions:

- Automated document review

- Generation of case chronologies

- Identification of gaps in oral evidence

-

Filtering and prioritization of legal arguments

These functions, traditionally time-consuming and labor-intensive, can now be executed with remarkable speed and precision through AI tools. He noted that this not only improves efficiency but also allows legal professionals to focus on more substantive and strategic aspects of arbitration.

Justice Venkatesh concluded his remarks by posing a thought-provoking idea:

“The final challenge may well be AI becoming an Arbitrator itself.”

He underscored that while technology has long served as a supportive tool, AI is poised to become an active stakeholder, potentially influencing and even transforming the arbitral decision-making process.

Continuing the thought-provoking discussion on technology in arbitration, Justice Vikram Nath turned to Mr. Tim Lord KC with a pertinent question on the intersection of blockchain technology and confidentiality:

“Blockchain is increasingly being used for secure record-keeping, document authentication, and smart contracts that can auto-trigger arbitration upon default. Given blockchain’s inherent transparency, how do we reconcile it with arbitration’s commitment and statutory requirement to maintain confidentiality?”

Mr. Tim Lord KC began with a candid admission of not being overly “technically smart,” drawing a warm chuckle from the audience. However, his response that followed was sharply analytical and insightful.

He structured his answer around three key points:

1. Contractual Consent to Arbitration

Mr. Tim emphasised that in most blockchain-based commercial arrangements, particularly those involving smart contracts, parties typically pre-agree to arbitration as the dispute resolution mechanism. This contractual consent effectively builds in recognition of confidentiality obligations from the outset.

He acknowledged, however, that identifying the actual parties to the dispute in complex, decentralized blockchain networks could pose challenges, especially in multifaceted or multi-party arrangements. Nevertheless, he stressed that such challenges are procedural and not insurmountable.

2. Role of the Arbitral Tribunal in Enforcing Confidentiality

Mr. Tim underlined the crucial role of arbitral panels in rigorously policing and enforcing confidentiality, particularly in blockchain disputes where the variegated commercial interests of participants may complicate proceedings.

3. Established Exceptions to Confidentiality

He pointed out that confidentiality, while integral to arbitration, is not absolute. There are already well-established exceptions, for instance, disclosure in the public interest or where required in related proceedings. These flexibilities, he noted, can be relied upon to navigate the complexities introduced by blockchain technology.

In conclusion, Mr. Tim expressed confidence that arbitration as a process has the resilience and adaptability needed to accommodate blockchain-based commercial disputes, provided tribunals remain proactive in addressing the evolving challenges of technology.

Continuing the session’s deep dive into emerging technologies, Justice Vikram Nath directed the next question to Mr. Mark Dempsey SC, focusing on the practical use of AI in reducing delays while preserving the fairness of arbitral proceedings:

“AI is already being deployed for tasks such as document review, predictive analytics, and case management across arbitral institutions worldwide. In a preliminary sense, how far and in what ways can AI be integrated into arbitral proceedings to meaningfully reduce delays without compromising due process?”

Addressing the question of how AI can be meaningfully integrated into arbitration without compromising due process, Mr. Dempsey structured his response into three parts:

- What use could be made of AI

- What use should not be made of AI

-

How far AI integration should go

1. What Use Could Be Made of AI

Mr. Dempsey outlined several areas where AI can enhance the efficiency of arbitration proceedings, provided its use is accompanied by contractual agreement, institutional guidelines, legislative backing, and ethical transparency, including clear disclosure, as recommended in the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators’ Protocol and similar approaches adopted by courts like the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

Key areas where AI can be constructively applied include:

- Legal research and analysis

- Rapid review of voluminous documents and project records

- Data collation and preliminary case assessment

- Preparation of documents and presentations

- Forensic data analysis and establishing agreed factual matrices

- Support for joint expert conferral and fact summarisation

- Automated summaries of arguments or submissions

-

Award drafting and post-award consistency checks

He highlighted that, in institutional arbitrations, AI could drastically reduce delays in finalising and reviewing awards, a process that often suffers due to unavailability of tribunal members. Using AI to check for consistency, accuracy of citations, and formal compliance could reduce review times from months to minutes.

2. What Use Should Not Be Made of AI

While acknowledging AI’s immense potential, Mr. Dempsey also offered cautions on where its use would be inappropriate or problematic, including:

- Witness Evidence: AI should not generate or rephrase witness statements, particularly where the witness has direct knowledge of the facts.

- Expert Opinions: AI-generated expert analysis must not replace independent expert testimony without proper disclosure and leave of the tribunal.

-

Tribunal’s Reasoning: AI must not be used in place of human reasoning or adjudication by the tribunal. Doing so would represent a delegation of the tribunal’s core function, raising serious due process and enforcement concerns.

He underscored that AI must remain within the record and party submissions; using AI to conduct research beyond what has been submitted would violate the agreed scope of the tribunal’s jurisdiction.

However, he did acknowledge that if parties explicitly agree to submit their dispute to an AI-based decision-making platform, such as Arbytrust AI, then such delegation is contractually valid.

3. How Far Should AI Go?

In conclusion, Mr. Dempsey noted that the adoption of AI by lawyers, consultants, and courts is accelerating rapidly, but that regulatory frameworks, institutions, and judicial bodies are still catching up.

His remarks provided a balanced perspective, celebrating AI’s capability to improve procedural efficiency while firmly safeguarding the integrity, fairness, and human-centred nature of arbitration.

Bringing the discussion to one of the most pressing contemporary challenges in the interface between AI and arbitration, Justice Vikram Nath turned to Mr. Tushar Mehta, the Solicitor General of India, with a question grounded in recent international developments and practical concerns.

“In recent cases globally, arbitrators have come under criticism for relying on AI, including tools like ChatGPT to draft arbitral awards. In light of this, should Indian tribunals outright prohibit the delegation of core adjudicatory functions to AI? Or should we consider regulating such use through a framework of disclosure and oversight? This is especially critical given known issues such as AI hallucinations, including the fabrication of case law in pleadings and awards and algorithmic bias, which could distort factual or legal analysis in arbitral proceedings.”

Mr. Tushar Mehta offered a candid, grounded, and thought-provoking response. His remarks reflected both openness to innovation and a strong cautionary stance grounded in legal realism and constitutional values.

“I’m neither for the use of AI nor actively against it,” he began, “but I believe it is too early to take a definitive call on its role in adjudicatory processes.”

Mr. Mehta revisited the earlier analogy made by Justice N. Anand Venkatesh — distinguishing technological assistance from artificial decision-making. Drawing a parallel with a coffee machine:

- If a person selects a cappuccino from a machine, that is user-driven technology.

-

But if the machine decides what coffee you want, or worse, what you should have based on your health, that becomes AI-driven decision-making, which intrudes into personal choice.

Mr. Mehta firmly underscored the dangers of allowing machines to think on behalf of adjudicators, citing:

- Fake Judgments: AI tools like ChatGPT have fabricated citations and legal precedents in the past. While some have been caught, many may go undetected, undermining the reliability of awards and court decisions.

-

Algorithmic Bias: He expressed deep concern about systemic bias embedded in AI models, referencing a U.S. study where an AI tool used in adjudicating traffic violations was found to have a racial and gender bias, specifically, against women of color.

He warned that AI tools, by design, collect and replicate patterns from publicly available datasets, may already be contaminated with societal prejudices. If such algorithms are used in arbitration, they risk reinforcing, rather than removing, systemic injustices.

In closing, Mr. Mehta cautioned against rushing into AI-driven adjudication in India:

- AI can support research, drafting, and analysis;

-

But it must not replace human judgment in core adjudicatory functions.

This opening session of Day 2 at DAW 2025 laid the intellectual groundwork for the rest of the conference. Through a combination of forward-thinking optimism and principled restraint, the panel collectively advocated for a future where technology supports, but never overrides, the values of fairness, transparency, and human judgment in arbitration.

The session concluded with an engaging round of audience questions.

Session 2 | Seats of the Future: Actionable Steps for Enhancing the Indian Arbitration Ecosystem

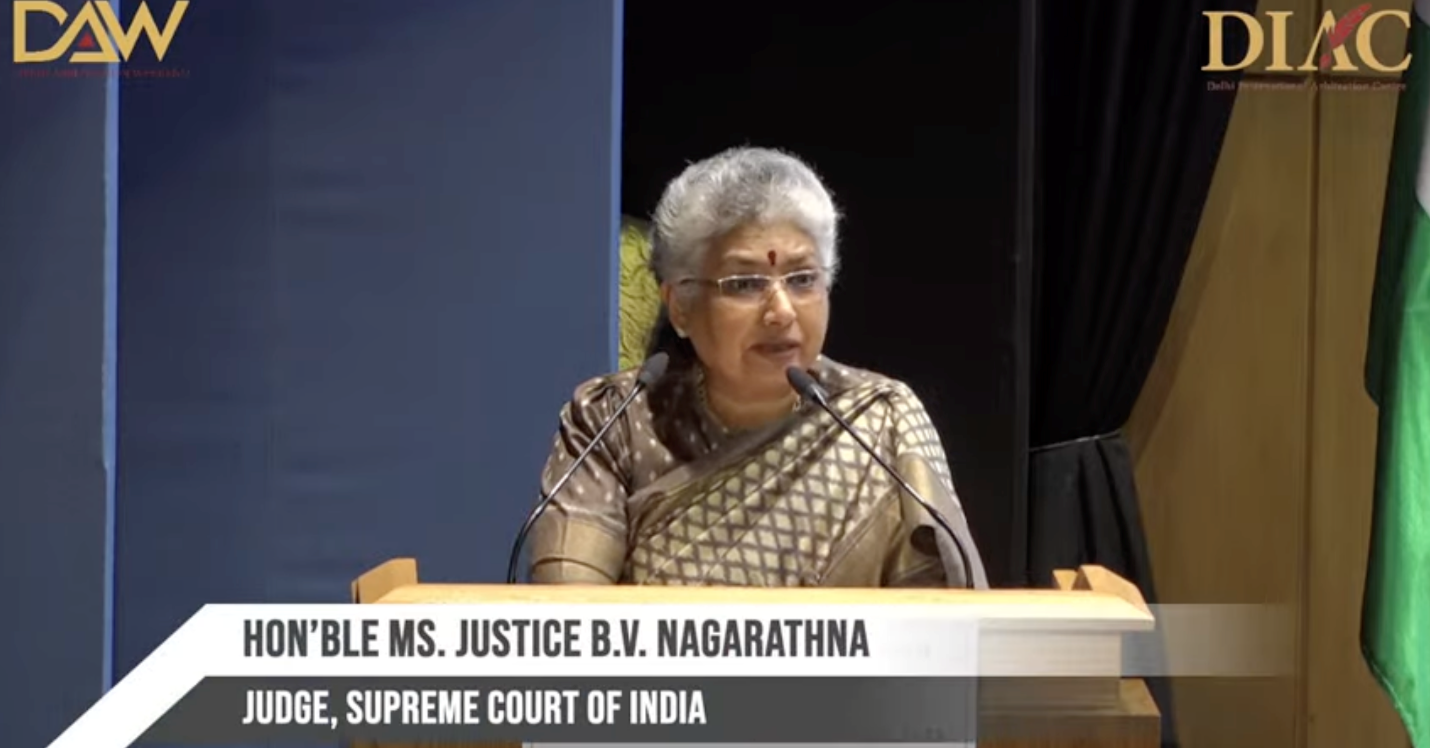

The second session of Day 2 at DAW 2025 focused on a critical and forward-looking theme: “Seats of the Future”, and explored actionable reforms and innovations needed to elevate India’s arbitration ecosystem to meet global standards. The discussion, chaired by Justice B.V. Nagarathna, Judge, Supreme Court of India brought together a distinguished panel of jurists, international arbitration experts, and reform-minded practitioners.

An esteemed panel of speakers contributed valuable perspectives:

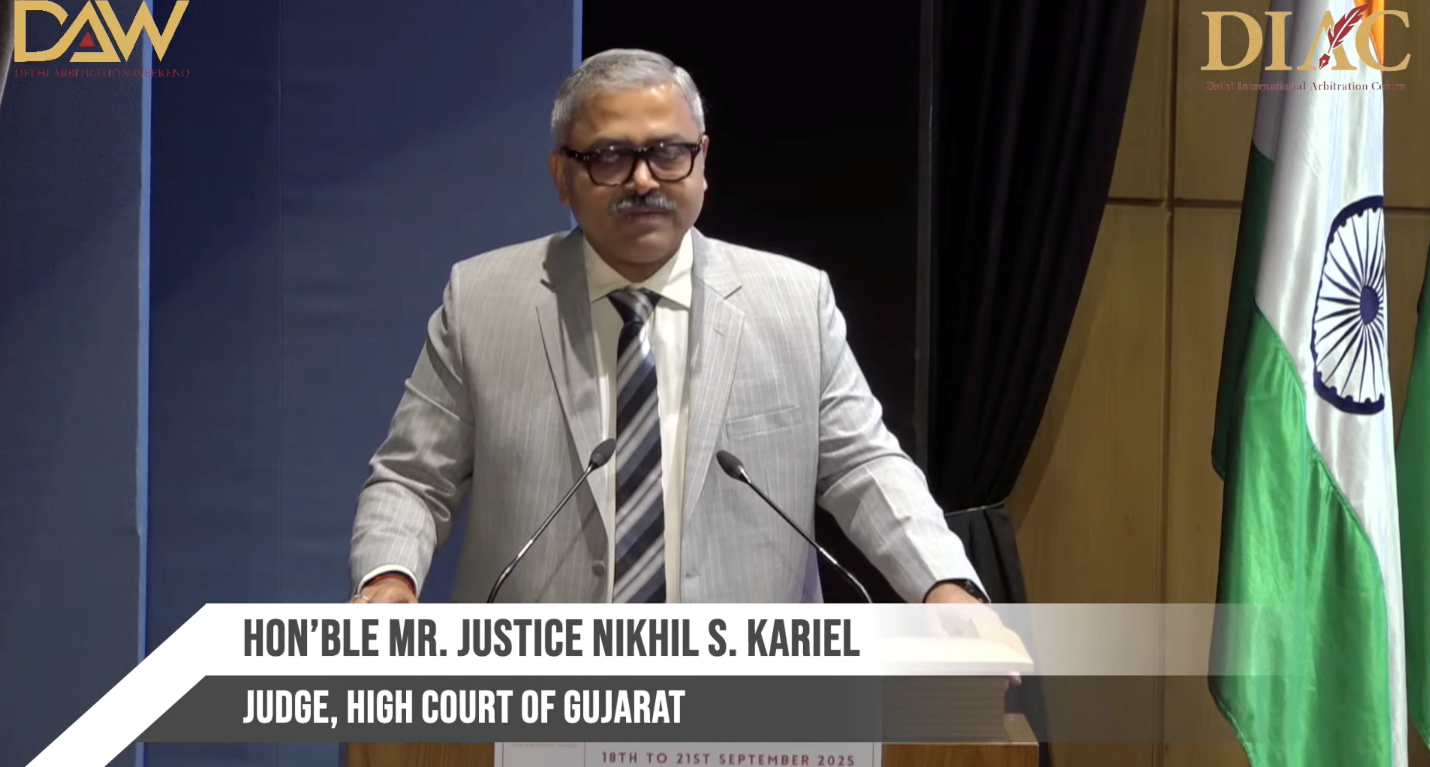

- Justice Nikhil S. Kariel, Judge, High Court of Gujarat

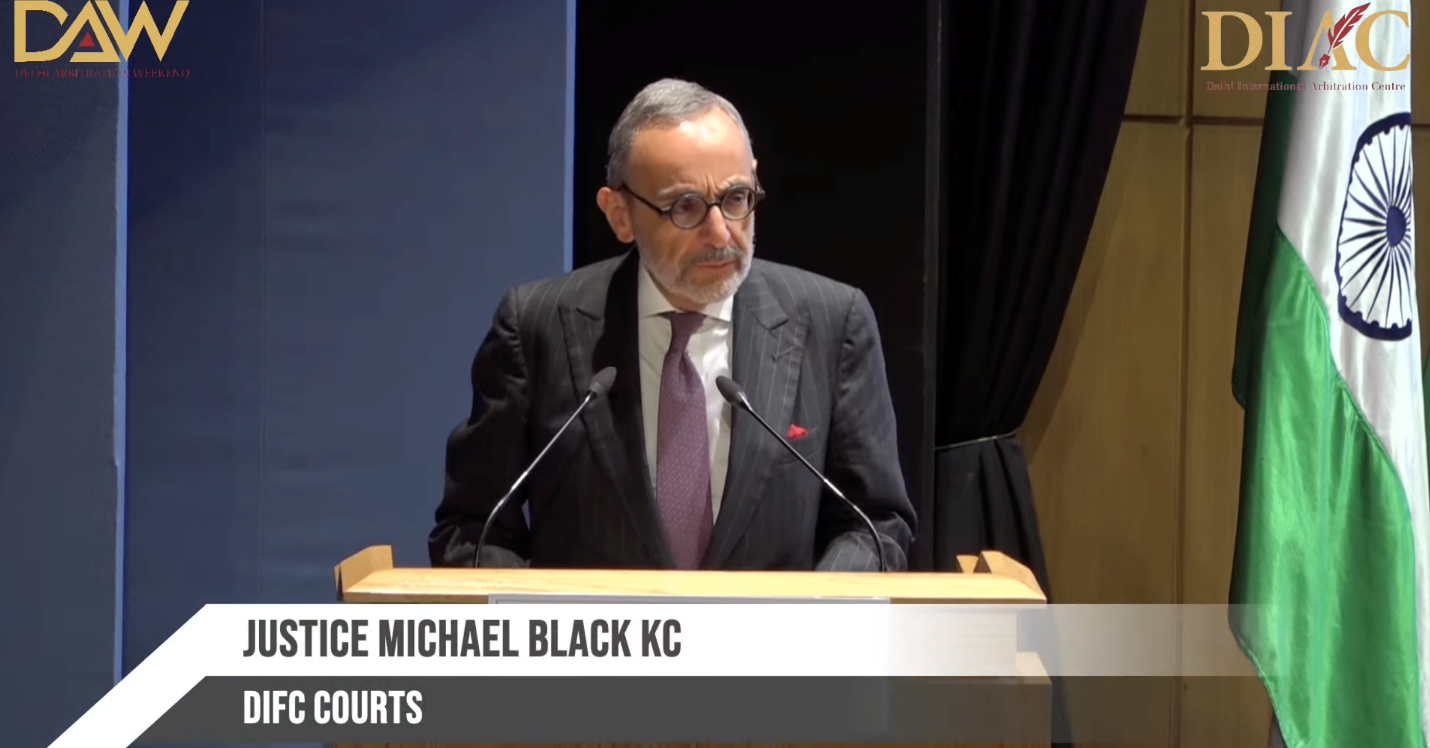

- Justice Michael Black KC, DIFC Courts

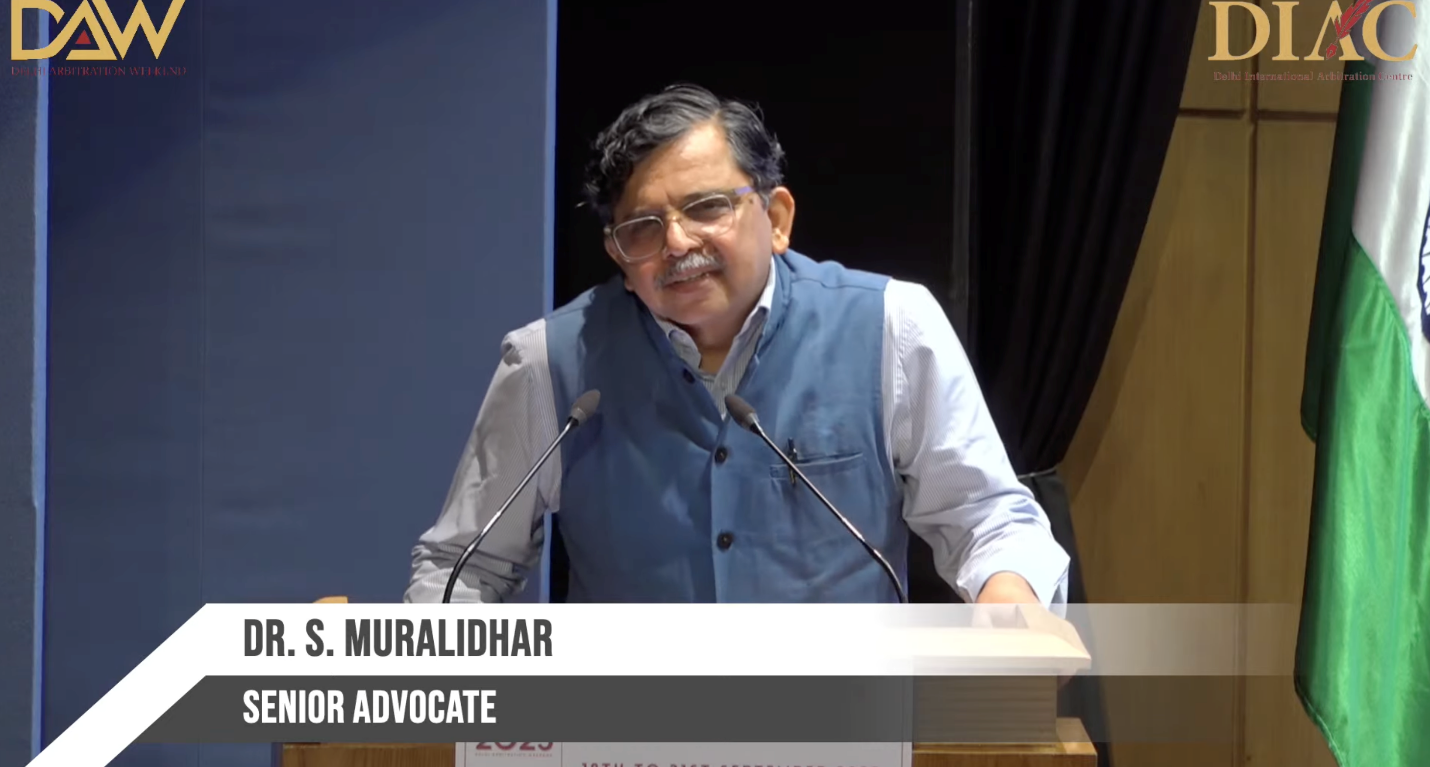

- Dr. S. Muralidhar, Former Chief Justice, Orissa High Court and Senior Advocate

-

Mr. David Quest KC, Barrister, 3 Verulam Buildings

Overview of the Chair’s Address:

Justice B.V. Nagarathna, Judge of the Supreme Court of India, opened Session 2 with a powerful and comprehensive keynote that offered both vision and pragmatism on how India can emerge as a global hub for arbitration. Her address struck a thoughtful balance between acknowledging challenges and offering constructive, actionable recommendations for improving the Indian arbitration landscape.

Justice Nagarathna began by highlighting the aspiration embedded in the session’s theme—that India has the potential to become a preferred seat for arbitration globally. However, she emphasized that such a transformation requires more than isolated reform; it calls for introspection and systemic overhaul across multiple fronts.

Judicial Intervention: A Double-Edged Sword

She candidly addressed the persistent concern over excessive judicial intervention, stating that even with a series of pro-arbitration rulings and legislative amendments (including those in 2015, 2019, and 2021), challenges to arbitral awards remain common. Citing studies showing over 40% of awards being set aside in certain High Courts, she noted that Section 34 and 37 proceedings often delay finality, thereby defeating the very objective of arbitration: efficient dispute resolution.

Yet, she clarified that judicial oversight is necessary but must be limited and principled. She reiterated that courts must support arbitration as a parallel, not subservient, mechanism of justice.

Quality and Integrity of Arbitrators

Justice Nagarathna placed strong emphasis on arbitral integrity and professionalism. She was unequivocal in stating that high-quality, well-reasoned awards reduce judicial intervention and bolster faith in arbitration. She called for a formal Code of Conduct for Indian arbitrators, ensuring adherence to standards of fairness, independence, neutrality, and timely disclosures of conflicts of interest.

“For India to become a seat of the future, any myopic focus on a single stakeholder on issue would be insufficient in my view.”

While India has no shortage of legal talent, she stressed that professional excellence must be coupled with ethical commitment and procedural diligence. A well-drafted, fair, and reasoned award, she said, is the best defense against judicial interference.

“I wish to take this opportunity to re-emphasize the need for various stakeholders to collectively participate in the shared vision of making India a global hub for arbitration”

Diversity and Development of the Arbitration Bar

A passionate advocate for inclusion, Justice Nagarathna argued that arbitration should not be the exclusive domain of retired judges or senior lawyers. She called for a diverse and deep pool of arbitrators, including younger professionals, women, and non-lawyers with sector-specific expertise. She hailed the establishment of a dedicated Arbitration Bar of India as a step in the right direction, recognizing the need for career arbitrators and not merely weekend practitioners.

“A successful arbitration hub needs a deep-pool of skilled professionals, and this involves continuous investment into the growth, upskilling and professional development of the next generation. In this regard, I think that establishment of a dedicated Arbitration bar of India is an incredibly favorable step”

Timelines, Costs, and Efficiency

Justice Nagarathna briefly touched on the issues of delays and costs, acknowledging them as significant roadblocks. She maintained that while India offers cost-effective arbitration compared to foreign jurisdictions, this advantage is nullified if proceedings are protracted. She encouraged the imposition of realistic timelines and cost deterrents against frivolous challenges.

Institutional vs Ad Hoc Arbitration

She raised the urgent need to transition from ad hoc to institutional arbitration, pointing out that India still largely operates in an unstructured, ad hoc environment. Institutional arbitration, she said, brings with it the benefits of predictability, professional case management, enforceable rules, vetted arbitrators, and procedural certainty. She called for strengthening and popularizing institutions like ICA, MCIA, IIAC, and DIAC, and promoting specialized institutions for niche areas such as technology law.

Mediation as a Parallel Path

An innovative idea Justice Nagarathna floated was to promote mediation within the arbitration process, especially through multi-tiered dispute resolution clauses. She suggested institutional arbitration centers should offer parties the option of mediation, facilitated by qualified mediators, thereby expediting resolution in appropriate cases and preserving business relationships.

A Collective Vision for the Future

Justice Nagarathna concluded her address with a clarion call for collective action. She emphasised that building a robust arbitration ecosystem requires synergy between judiciary, legislature, arbitrators, practitioners, and institutions. The desired attributes, finality, structure, credibility, efficiency, and legitimacy are interlinked, and dependent on a combination of judicial restraint, technological adoption, and infrastructure development.

Reaffirming her optimism, she declared that India can and must become a preferred seat of arbitration, and that with commitment, innovation, and accountability, that future is well within reach.

After this insightful opening, Justice Michael Black KC, DIFC Courts, delivered a globally contextual and insight-rich address, drawing from his two decades of experience as an Arbitrator in India and his broader international practice. He refrained from making prescriptive comments on the Indian legal system but instead framed his discussion around universally accepted benchmarks for an arbitration-friendly seat, anchored in the London Centenary Principles (2015) developed by the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb). His remarks reflected deep respect for the Indian legal fraternity, alongside a candid and comparative assessment of the features that make arbitration systems efficient, credible, and globally attractive.

Characteristics of an Arbitration-Friendly Jurisdiction: Lessons from the London Centenary Principles

Justice Black outlined ten foundational principles for a jurisdiction aspiring to be an effective seat of arbitration:

1. Modern Arbitration Law

A jurisdiction must have a clear, modern arbitration law that:

- Respects party autonomy,

- Minimizes court interference, and

-

Balances transparency and confidentiality.

He acknowledged that India, through the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, along with subsequent amendments, meets global standards in this regard.

2. Judiciary

A competent, efficient, and arbitration-respecting judiciary is vital. He emphasised that courts should not view arbitration as “Alternative Dispute Resolution”, but rather as “Appropriate Dispute Resolution”, echoing the original conception from the Harvard Pound Conference (1975).

Critically, he addressed a misconception in many jurisdictions: courts often wrongly perceive arbitration as a competitor, whereas, under the seat theory, they are supporting institutions, crucial to the arbitral process itself.

3. Legal Expertise

Justice Black praised Indian legal professionals for their exceptional competence, asserting that they rival their global peers in both substance and style.

4. Judicial Statistics on Challenges to Awards

Offering a valuable comparative lens, he cited data from the English Commercial Court. He contrasted this with Indian data highlighting India’s higher intervention rates as a cause for concern.

He briefly touched on the remaining CIArb principles:

- Education: Robust training and awareness among all stakeholders.

- Right of Representation: Parties must be allowed to choose their representatives (including non-lawyers).

- Accessibility and Safety: Visa issues and access limitations can undermine a jurisdiction’s attractiveness (noting challenges Indian lawyers have faced in the UK).

- Functional Facilities: Arbitration centres must be world-class and easily accessible.

- Ethics: Development of international ethical norms across legal cultures.

-

Enforceability: Adherence to global treaties (like the New York Convention).

Institutional vs Ad Hoc Arbitration: A Practitioner’s Perspective

Drawing from personal experience, ad hoc arbitrations in India vs institutional ones globally, Justice Black offered ten reasons institutional arbitration is more efficient, predictable, and fair:

- Transparent and Predictable Costs

Institutions offer upfront cost estimates, helping parties manage expenses. - Structured Appointment and Challenge Process

Institutions offer tested frameworks for appointing or challenging Arbitrators—avoiding delays and court interference. - Pre-Set Procedural Rules

Institutional rules minimize disputes about process and streamline timelines. - Secretarial Support

Institutions handle admin tasks including tax compliance, logistics, and procedural oversight. - Quality Control of Arbitrators

Institutions can subtly guide parties toward appointing qualified and credible Arbitrators, discouraging repeated appointment of underperforming individuals. - Support in Drafting Enforceable Awards

Institutions like ICC and SIAC assist in scrutinizing awards for enforceability—e.g., ICC involves legal experts from target jurisdictions to ensure compatibility. - Award Scrutiny

Formal scrutiny processes catch technical or procedural flaws, thereby reducing chances of court challenges. - Tax and Financial Assistance

Especially valuable for cross-border Arbitrators dealing with foreign tax systems. - Institutional Knowledge and Precedent

Long-standing institutions accumulate best practices, benefiting both counsel and Arbitrators. -

Client-Centric Efficiency

At the end of the day, institutional arbitration better serves businesses and clients, who are the true stakeholders of the system.

“Institutional arbitration really does have very, very significant advantages over ad hoc arbitration, and that is perhaps a goal that this jurisdiction might perhaps aim at.”

-Justice Michael Black KC, DIFC Courts

Justice Black concluded by strongly advocating for India to embrace institutional arbitration as a structural reform objective.

Justice Michael Black KC’s address was a masterclass in comparative arbitration systems, offering valuable benchmarks rooted in global best practices, without being prescriptive about Indian reform. His reflections on seat theory, judicial restraint, institutional knowledge, and client-centric arbitration provided clarity and vision to India’s evolving arbitration ecosystem.

Taking the floor with both clarity and conviction, Justice Nikhil S. Kariel emphasised that arbitration is no longer peripheral; it is central to global commerce and must be treated as such within India’s legal and institutional frameworks.

Positioning arbitration as a “necessity, not an alternative,” he raised a fundamental question: “Why not India?” Despite its increasing economic stature and commercial significance, India continues to face skepticism from international parties due to systemic inefficiencies, procedural delays, and inconsistent judicial intervention. To address this, Justice Kariel drew inspiration from John Dewey’s observation that “a problem well stated is a problem half solved,” and proceeded to identify five core issues plaguing the Indian arbitration landscape:

- Dominance of Ad Hoc Arbitration

Ad hoc proceedings in India often lack standardized procedures, timelines, or fee structures, resulting in unpredictability, delays, and cost escalations. - Absence of Structured Timelines

Despite statutory deadlines, extensions are frequently granted. Unlike jurisdictions such as Singapore or Hong Kong, India lacks a culture of strict time-bound compliance. - Cumbersome Execution of Awards

Treating arbitral awards as civil decrees brings them back into the congested civil litigation system, thereby undermining the speed and finality expected from arbitration. - Excessive Judicial Interference

Although judicial review plays a necessary role in safeguarding fairness, overreach—especially through constitutional provisions—has weakened party autonomy and discouraged international confidence. -

Concerns About Arbitral Quality

Justice Kariel voiced concern over poorly reasoned or even plagiarized awards and cited a case where one arbitrator’s reasoning in one tribunal influenced another’s award before it was even formally issued. He argued that such issues underscore the need for judicial oversight in truly exceptional circumstances, to preserve integrity without undermining arbitration’s autonomy.

Transitioning to remedies, Justice Kariel laid out a six-point reform agenda:

- Institutionalisation of Arbitration

Strongly advocating for institutional arbitration, he urged the creation and promotion of professional arbitral centres, with private sector involvement, structured rules, and panel accreditation. Making institutional arbitration mandatory for certain categories of disputes was also suggested. - Upholding Quality and Integrity

He recommended that arbitral institutions enforce eligibility norms, scrutiny of draft awards, and disclosure of multiple concurrent appointments, while encouraging specialization and accountability. - Hands-on Yet Restrained Judicial Approach

Emphasising that minimal interference is not abdication, he called for specialized arbitration benches, consistent jurisprudence, and judicial training to balance autonomy with accountability. - Accelerated and Phased Procedures

Drawing on SIAC’s expedited procedures and the innovations in the 2025 SIAC Rules, Justice Kariel proposed structured stages in arbitration: fixed timelines for appointments, limited hearings, and stricter deadlines for award delivery,mirrored in the 2024 Indian Draft Arbitration Bill. - Reformed Enforcement Mechanisms

Enforcement delays, largely due to civil procedure complexities and overuse of the public policy ground, must be addressed. He suggested statutory timelines, dedicated arbitration benches, e-filing, and digital tracking to streamline enforcement. -

Costs and Sanctions Against Frivolous Challenges

To prevent delay tactics and misuse of appeals, he welcomed the Draft 2024 Bill’s proposal for a specialized appellate tribunal, provided it is invoked by agreement, and helps curtail challenges under Sections 34 and 37 of the Arbitration Act.

In conclusion, Justice Kariel offered a call to action: India’s arbitration potential is immense, but realisation demands reform. By institutionalising arbitration, enhancing procedural discipline, ensuring award quality, and introducing smarter enforcement mechanisms, India can emerge as a globally credible and competitive arbitration seat.

“While the world looks to London, Singapore and Paris, there is no reason why it should not look to India tomorrow. Let us move forward this with courage, clarity and resolve for it is through thoughtful reform that India can claim its rightful place as a global hub of arbitration.”

Following Justice Nikhil S. Kariel’s incisive analysis of the structural challenges and reform imperatives facing the Indian arbitration ecosystem, Mr. David Quest KC addressed the panel and audience with a forward-looking perspective on the rapidly evolving domain of technology-driven disputes.

Highlighting the remarkable growth of the digital economy, Mr, Quest noted that cryptocurrencies alone have expanded from a nascent concept in 2009 to a market capitalization exceeding $3 trillion, a figure that underscores both the scale and resilience of this sector despite significant volatility and numerous instances of insolvency and fraud. This rapid expansion has precipitated a surge in complex commercial disputes, many of which are increasingly resolved through arbitration. Given India’s prominence as a technological powerhouse, Quest emphasized that the country should anticipate a significant influx of arbitrations related to novel technology issues.

Quest underscored that digital assets represent only one facet of a broader wave of disputes involving emerging technologies such as smart contracts, blockchain platforms, algorithmic trading, and artificial intelligence. These disputes are distinguished not only by their technical complexity but also by novel legal and procedural challenges. For instance, the rise of decentralized autonomous organizations, entities operating algorithmically without traditional legal form and corporate governance rights encoded in blockchain tokens, demand innovative approaches to dispute resolution.

He drew attention to the profile of contemporary disputants: often highly technical entrepreneurs who are accustomed to rapid technological innovation and express frustration with conventional arbitration processes perceived as overly procedural, time-consuming, and insufficiently technologically adept. These parties increasingly seek arbitrators possessing deep technological expertise not merely digital literacy but a nuanced understanding of blockchain architectures, smart contract operations, and decentralized governance models. Such expertise is critical both for assessing the substantive merits of disputes and for devising effective case management strategies, including disclosure and evidentiary procedures involving digital assets.

In response to these challenges, Mr. Quest introduced the work of the UK Jurisdiction Taskforce, an industry-led initiative supported by the UK government, which has developed a set of Digital Dispute Resolution Rules tailored specifically for technology disputes. These rules are intentionally concise, vesting substantial discretion in arbitrators to design bespoke procedures that are significantly expedited compared to traditional arbitration timelines. By condensing default timelines to days rather than months and maintaining a roster of qualified arbitrators ready for immediate appointment, the framework aims to address the need for speed and flexibility in resolving technology disputes.

Notably, the rules accommodate the unique characteristics of blockchain-based systems, recognizing on-chain dispute resolution mechanisms, including the capacity for arbitrators to enforce awards directly through control of private keys, thus enabling immediate execution on the blockchain. They also address issues of party anonymity, allowing parties who have transacted anonymously on blockchain platforms to remain so during arbitration while requiring disclosure to the tribunal.

Mr. Quest acknowledged that artificial intelligence poses emerging challenges both as a tool to enhance arbitration processes and as a source of disputes, particularly those arising from transactions and agreements formed by autonomous AI agents. He noted the necessity for continued development of legal frameworks and arbitral practices to manage AI-related disputes effectively.

While the Digital Dispute Resolution Rules are not the sole approach to these challenges and remain at an early stage of adoption, Quest proposed that their principles and innovations offer valuable insights for the Indian arbitration community. As India seeks to position itself as a global hub for arbitration, embracing procedural innovation and developing arbitrator expertise in emerging technologies will be essential to attract and effectively resolve disputes in the expanding digital economy.

In closing, Mr. Quest’s address reinforced the imperative for India not only to address existing systemic challenges but also to proactively adapt to the complexities of technology-driven disputes, thereby ensuring its arbitration framework remains both relevant and competitive on the international stage.

As the discussion progressed, building on the insightful perspectives around arbitration in the digital age and the evolving demands of cross-border dispute resolution, the conversation turned to a more introspective and systemic lens. Dr. S. Muralidhar, began by expressing his reservations about the use of the term “compete” in the context of making India an attractive arbitration destination. He emphasised that rather than positioning India in competition with other jurisdictions, the focus should first be on resolving the inherent issues within India’s domestic arbitration framework. According to him, addressing domestic challenges is a prerequisite to effectively attracting international arbitration matters.

Drawing on his extensive experience attending similar conferences over the years, Dr. Muralidhar highlighted the systemic and structural problems embedded in the Indian legal system that impede the growth of arbitration. He pointed out that the Indian judiciary and bar remain predominantly generalist in nature. Top lawyers and judges, including those present in the audience, routinely handle a wide array of cases,from criminal appeals and bail applications to matrimonial and arbitration disputes. This generalist approach restricts the development of specialized arbitrators and arbitration lawyers, which are essential for building a robust arbitration ecosystem.

Dr. Muralidhar further elaborated on the issue of litigating capacity. In international commercial arbitration, parties, counsel, and arbitrators dedicate exclusive, uninterrupted time to a single dispute. By contrast, Indian judges and lawyers often juggle multiple cases simultaneously across various domains, making it difficult to fully immerse themselves in complex arbitration matters. He stressed that this difference affects the nature and quality of dispute resolution and poses a challenge to fostering specialization in arbitration.

Dr. Muralidhar also addressed the challenges related to enforcement of foreign arbitral awards. He observed that Indian courts tend to scrutinize large foreign awards—particularly those involving government or public sector entities—more rigorously, which can lead to delays and uncertainty in enforcement proceedings.

Concluding his remarks, Dr. Muralidhar emphasised the need to develop indigenous arbitration systems tailored to India’s unique legal culture and practices. He cautioned against uncritical adoption of international models such as the UNCITRAL Model Law, which are designed for jurisdictions with different procedural norms, including stricter adherence to timelines and cost controls. Instead, he called for thoughtful adaptation of such frameworks to the Indian context.

To illustrate his point, Dr. Muralidhar drew a parallel with India’s success in medical tourism, attributing it to the country’s demonstrated excellence and reputation rather than aggressive marketing. He suggested that similarly, India’s arbitration ecosystem can attract international parties organically if it first builds specialization and expertise within its domestic system.

In closing, Dr. Muralidhar urged all stakeholders to focus on strengthening the domestic arbitration framework by fostering specialized arbitration bars and specialized judges. He expressed confidence that once India’s “house is in order,” other aspirations for international arbitration prominence would naturally follow.

Session 2 offered a compelling tapestry of perspectives, drawing from global experience, institutional insight, emerging technologies, and grounded reflections from within the Indian legal system.

Session 3 | Appointment of Arbitrators: Party Autonomy Conundrum

Session 3 of DAW 2025 brought together eminent jurists, scholars, and practitioners to deliberate on the enduring tension between party autonomy and the need for impartiality, transparency, and fairness in the appointment of arbitrators, a subject that continues to spark global debate in the evolving arbitration landscape.

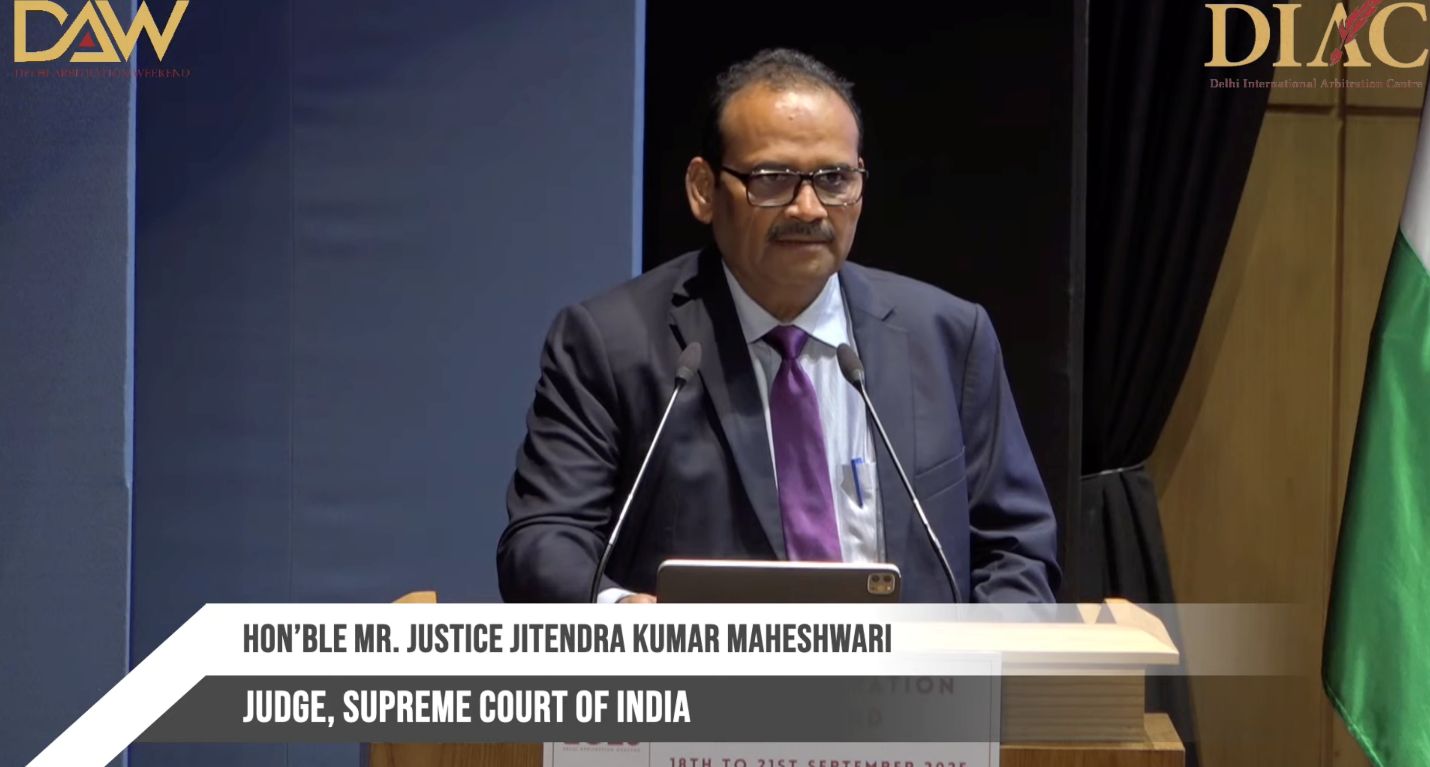

The session was chaired by Justice Jitendra Kumar Maheshwari, Judge, Supreme Court of India, who opened the discussion by highlighting the delicate balance between party autonomy, a foundational principle of arbitration and the imperative of fairness and impartiality in the appointment of arbitrators.

An esteemed panel of speakers contributed valuable perspectives:

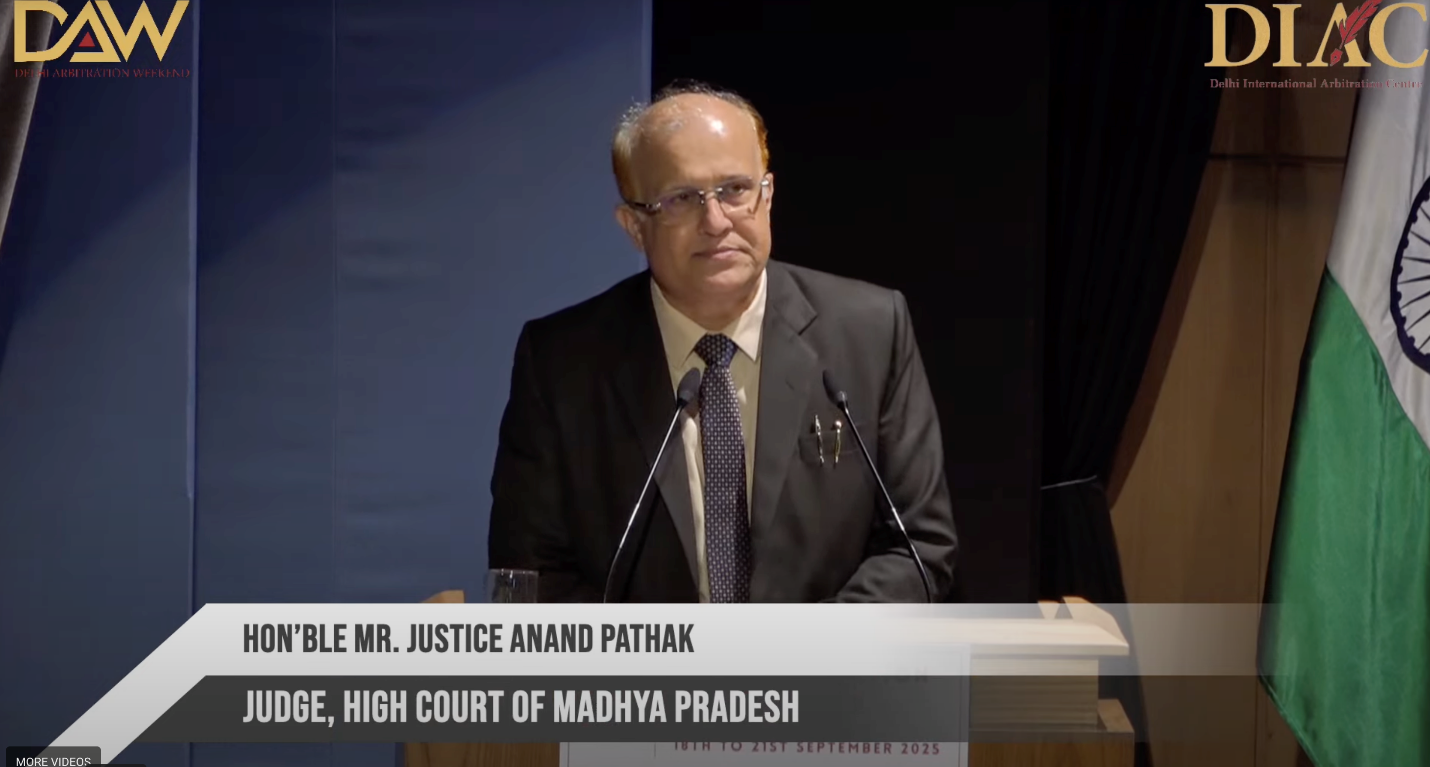

- Justice Anand Pathak, Judge, High Court of Madhya Pradesh

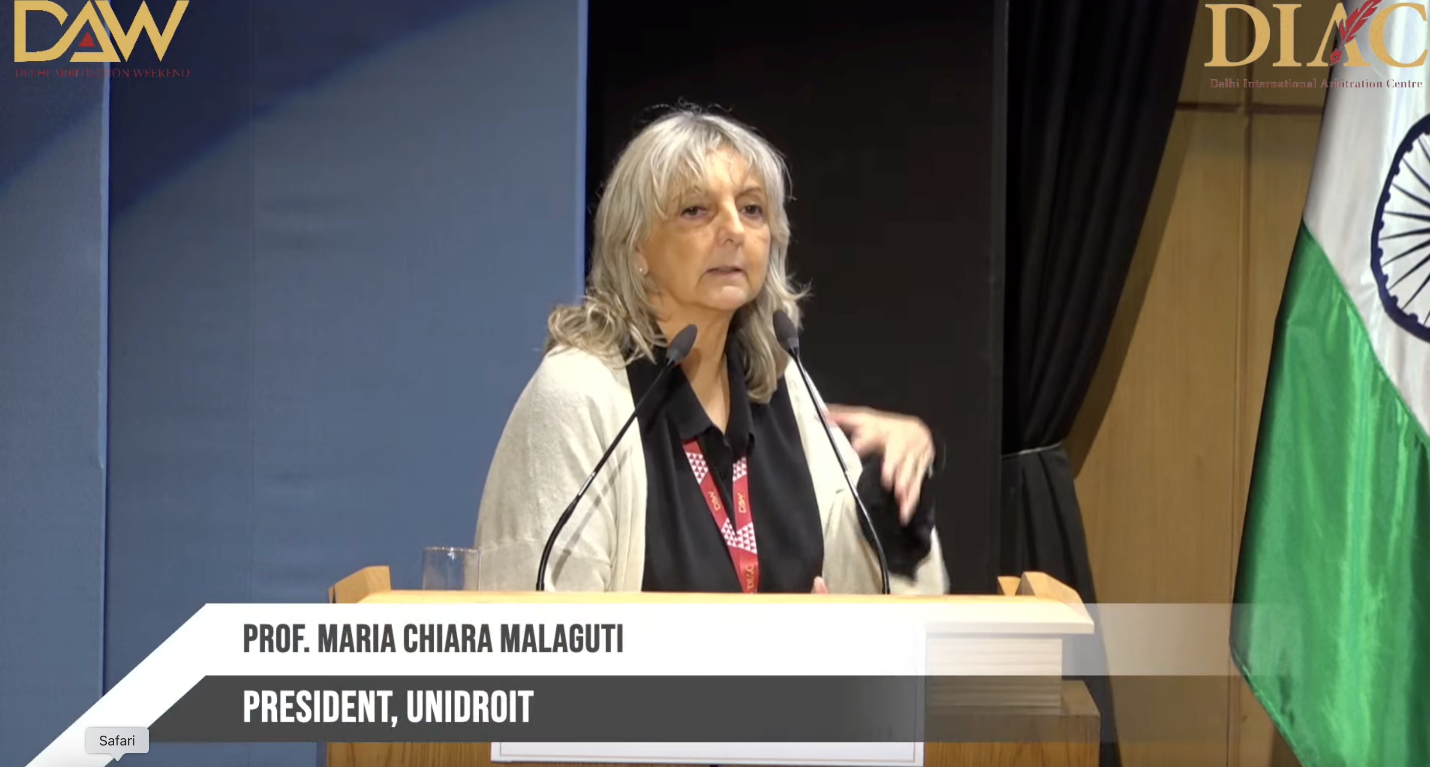

- Prof. Maria Chiara Malaguti, President, UNIDROIT

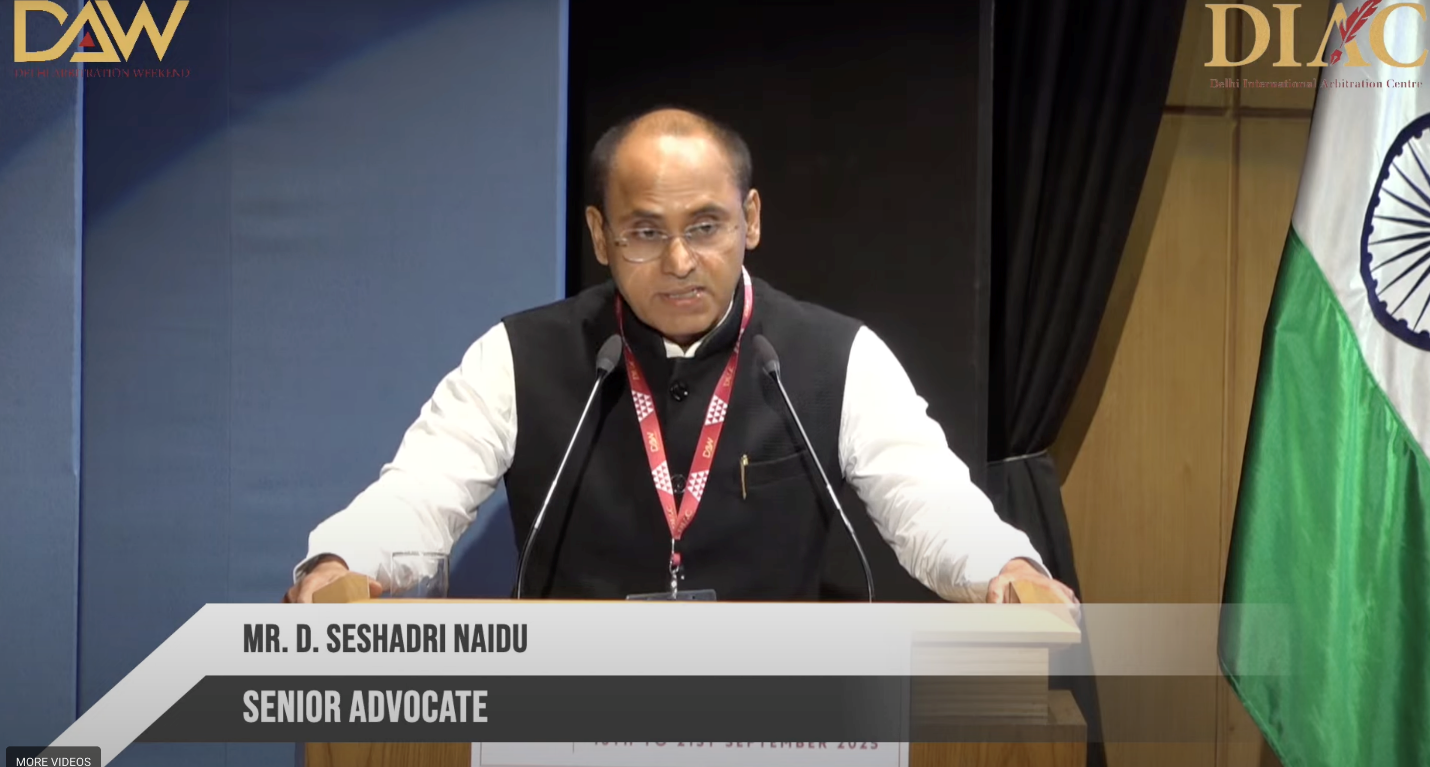

- Mr. D. Seshadri Naidu, Senior Advocate

-

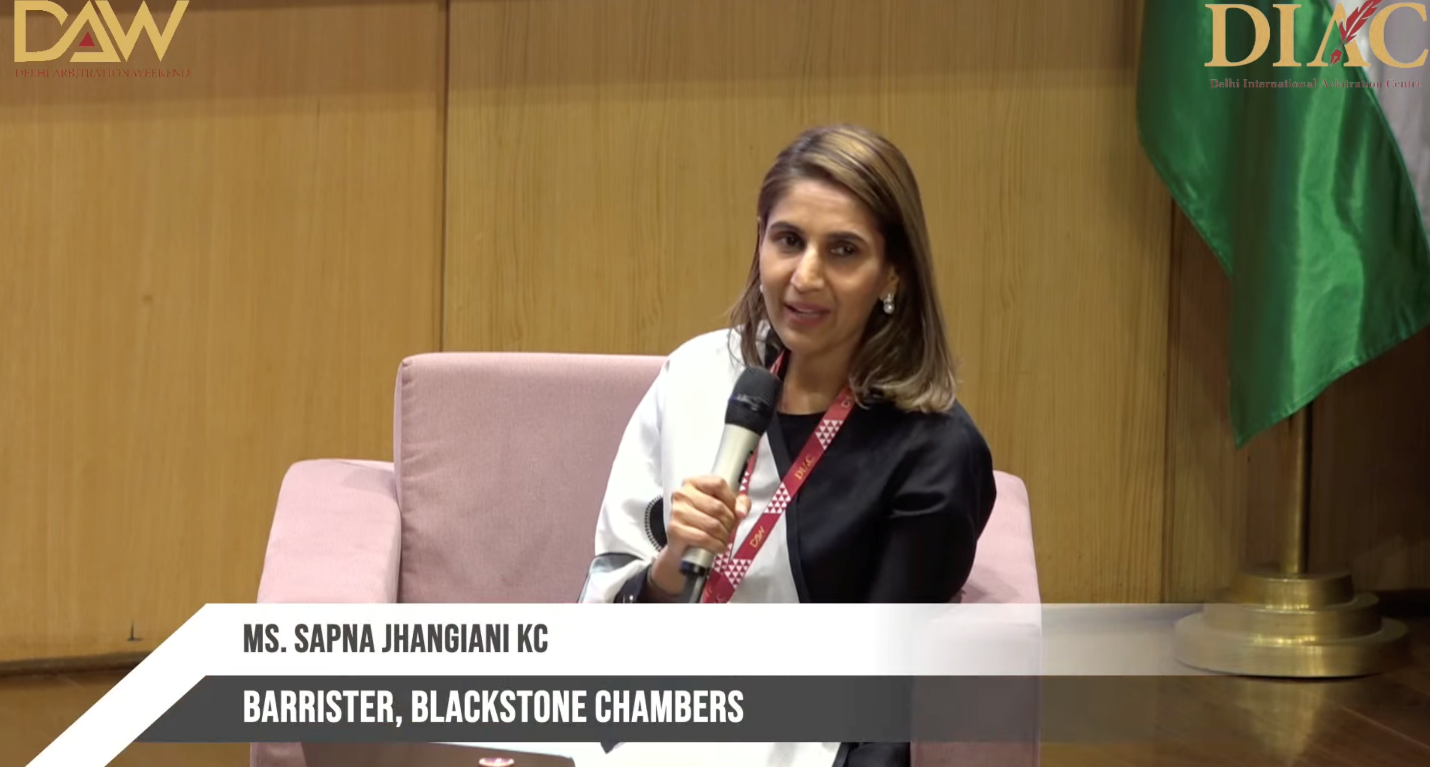

Ms. Sapna Jhangiani, Barrister, Blackstone Chambers

Justice Jitendra Kumar Maheshwari opened the session by warmly welcoming the audience to this significant discussion set against the backdrop of New Delhi’s growing stature as a global arbitration hub. He reflected on the enduring charm of arbitration, which lies in its core promise of efficiency, expertise, and procedural autonomy, allowing parties to select their adjudicators and shape the dispute resolution process in alignment with commercial realities.

He emphasised that party autonomy, the foundational principle of arbitration, empowers disputing parties to choose their arbitrators and design tailored procedures. However, this autonomy must be carefully balanced with the principles of fairness, equality, independence, and impartiality. This inherent tension between respecting the sanctity of contractual choice and upholding procedural integrity forms the core challenge that today’s session seeks to explore.

Justice Maheshwari questioned whether courts should uphold arbitration clauses that seemingly undermine neutrality and equal treatment, particularly when they allow one party disproportionate control over the appointment of arbitrators. He noted that this issue frequently arises in contracts drafted by parties with greater financial or bargaining power, leading to clauses that raise serious concerns about impartiality, especially when arbitrators are affiliated with the appointing party.

Referring to legislative reform in India, he highlighted Section 12(5) introduced via the 2015 Amendment to the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, along with Schedules 5 and 7, which together aim to strike a balance between party autonomy and institutional integrity by setting clear standards for independence and disclosure.

Justice Maheshwari concluded by affirming that while party autonomy is vital, it cannot be absolute. It must be exercised within a framework that upholds due process, procedural fairness, and public policy. Achieving this balance requires coordinated efforts from lawmakers, courts, arbitral institutions, and practitioners, ensuring that arbitration in India evolves with global best practices while maintaining its credibility and legitimacy.

Continuing the discussion, Justice Anand Pathak, Judge, High Court of Madhya Pradesh, emphasised the delicate balance between party autonomy and institutional safeguards in arbitration, particularly in the context of arbitrator appointments. He noted that while party autonomy is a fundamental tenet of arbitration, allowing parties the freedom to decide the substantive law, procedural rules, and composition of the tribunal, this freedom must be exercised within the framework of fairness and equality, especially when viewed through the lens of Section 12(5) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act.

Justice Pathak stressed that party autonomy cannot be interpreted as absolute, particularly in situations where contracts are drafted by financially or institutionally dominant parties. He provided examples from consumer finance sectors and public-private partnerships, where arbitration clauses are often one-sided and inherently skewed in favour of one party, thereby undermining the very premise of neutrality and fairness.

Justice Pathak also delved into the importance of arbitrator conduct, highlighting that the duties of an arbitrator, to act impartially, judicially, and judiciously are integral to upholding the sanctity of the arbitral process. He cautioned against various cognitive biases that may inadvertently influence arbitrators’ decisions and proposed that psychological training, structured evaluation mechanisms, and continuous professional development could serve as vital tools in maintaining the integrity and quality of arbitral awards.

He concluded by affirming that effective arbitration depends not only on party freedom but equally on the ethical and intellectual rigour of the arbitrators. Therefore, a reimagining of both contractual practices and capacity-building efforts is essential to strengthen India’s credibility as a reliable and fair arbitration jurisdiction.

Taking the podium next, Mr. D. Seshadri Naidu, Senior Advocate, brought a compelling and philosophical perspective to the debate on party autonomy in arbitrator appointments, describing the very theme of the session as inherently paradoxical. He began by highlighting the contradictory nature of the phrase “autonomy conundrum”, noting that while autonomy suggests clarity and decisiveness, a conundrum implies ambiguity and doubt, thereby reflecting the core tension between freedom of choice and the need for fairness in arbitral proceedings.

Referring to guidance given by the session Chair in preparatory discussions, Mr. Naidu addressed two pivotal questions:

-

How far does party autonomy extend before it must yield to judicially mandated safeguards of impartiality under Section 12(5) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act?

-

Can an arbitral award be set aside post-facto on grounds of unilateral appointment if no objection was raised during the proceedings?

Blending legal analysis with literary references, Mr. Naidu creatively invoked Shakespeare’s Hamlet—“To be or not to be”—to explore the question: To choose or not to choose one’s own arbitrator? He emphasised that impartiality is the bedrock of justice, and that any process where an arbitrator is effectively imposed by the opposing party undermines that very foundation.

Mr. Naidu examined the doctrine of bias under common law, noting its origins in tightly knit societies like medieval England, where connections and conflicts of interest were more visible. However, in a vast and complex society like India, he argued, applying the same rigid parameters without contextual calibration may not be entirely appropriate.

Mr. Naidu concluded by describing this arbitration debate as an evolving legal frontier, where statutory fidelity must be balanced with fairness, impartiality, and constitutional morality. He advocated for deeper reflection on how far party autonomy should go, and suggested that structural inequality in bargaining power, particularly in public contracts, must be addressed through legal and institutional reform.

Prof. Maria Chiara Malaguti, Professor of International Law and President of UNIDROIT, brought a distinctly international and comparative dimension to the panel with her address. Drawing upon her deep involvement in UNCITRAL negotiations on investment arbitration, she examined the evolving tension between party autonomy and the need for institutional safeguards, particularly around the independence and impartiality of arbitrators.

Prof. Malaguti began by emphasising the significance of the session’s topic, calling it one of the most critical issues in contemporary arbitration. She took the audience on a legal and conceptual journey, starting with arbitration’s private, community-based origins, and tracing its shift towards a quasi-judicial framework, especially in light of recent developments in investment arbitration. Highlighting the adoption of the Code of Conduct for Arbitrators at UNCITRAL, she reflected on how soft law instruments are already reshaping expectations of arbitrator neutrality and procedural fairness across jurisdictions.

Following this, Ms. Sapna Jhangiani drawing on over 25 years of experience in international arbitration, offered a comprehensive examination of the conceptual tensions surrounding party autonomy and the unilateral appointment of arbitrators. Beginning with the landmark CORE judgment, she highlighted the valuable insights from Justice Narasimha’s dissent, which surveyed diverse foreign legislation and case law on the issue.

Ms. Jhangiani detailed how statutes in countries like Spain, Germany, and Estonia permit courts to intervene where one party has an unfair advantage in tribunal appointments, while international instruments like the European Convention on Arbitration invalidate agreements that privilege one party in appointing arbitrators. She contrasted the liberal French approach with more restrictive rulings in Switzerland, the U.S., and the U.K., where courts have struck down arbitration clauses granting one party exclusive or disproportionate control over arbitrator selection, citing concerns over neutrality, fairness, and bias.

She then expanded the discussion to the conceptual level, questioning whether the conflict often framed between party autonomy and principles like impartiality or public policy might instead be understood through the lens of vitiated consent, especially in contexts of unequal bargaining power. Ms. Jhangiani drew parallels to developments in consumer arbitration law, noting how courts in jurisdictions such as the UK, Canada, and the EU are increasingly scrutinizing arbitration agreements in consumer and digital economy contracts for fairness and genuine consent.

Ms. Jhangiani concluded with a call to vigilance: as arbitration expands into new fields and consumer contracts, practitioners and courts alike must continually ask how truly “free” parties are in their arbitration choices.

Session 3’s rich discussion has illuminated the delicate balance at the heart of arbitration: safeguarding party autonomy while ensuring fairness, impartiality, and true consent. From the nuanced debates on unilateral arbitrator appointments to the evolving challenges posed by unequal bargaining power, we have seen that arbitration is not a static concept but a living framework that must continuously adapt.

Session 4 | Investment Arbitration at a Crossroads: Key Developments, Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Session 4 focused on the evolving landscape of investment arbitration, a field that has increasingly found itself at a crossroads amid global calls for reform, greater transparency, and recalibration of investor-state relations.

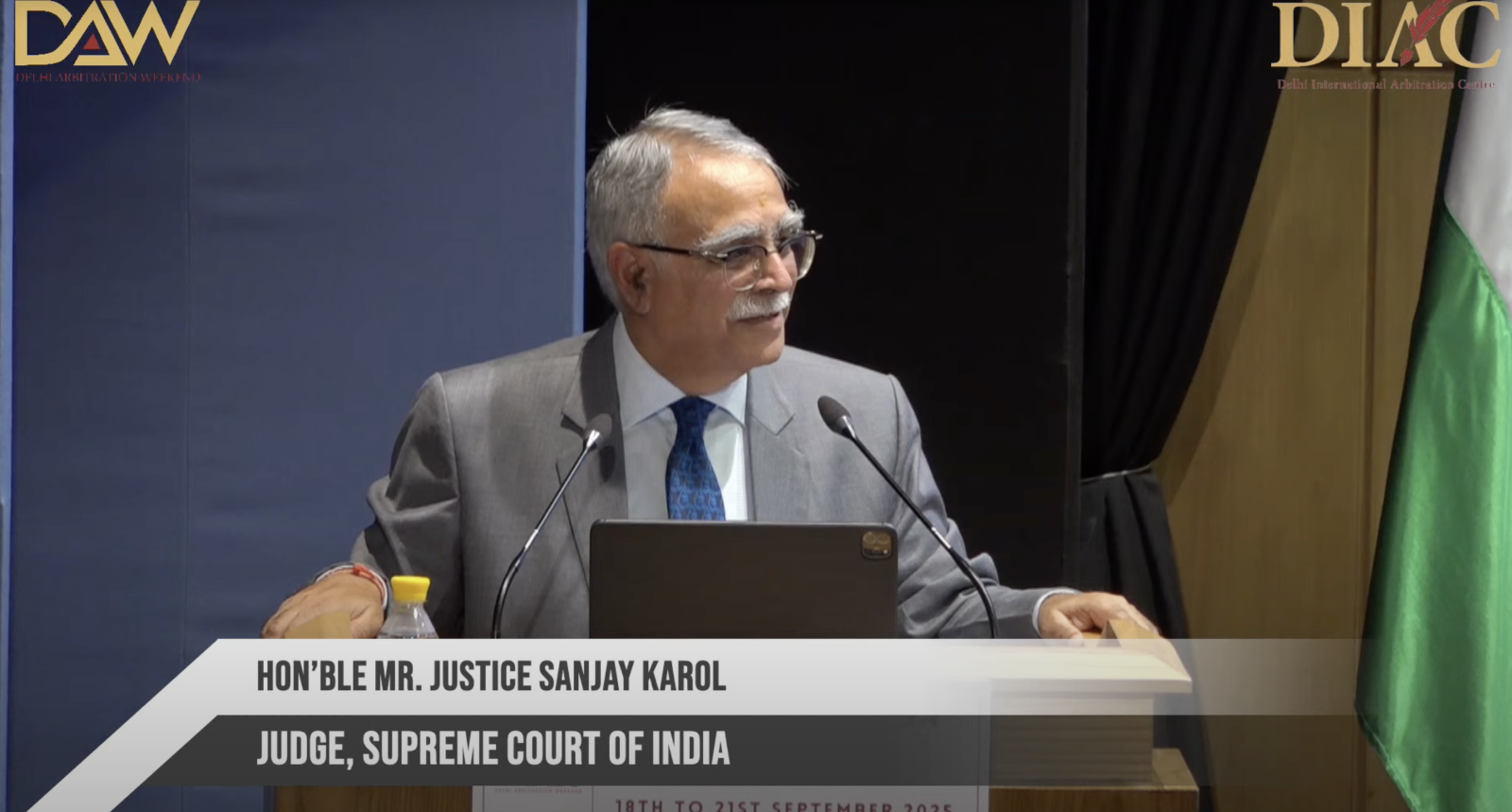

The session was chaired by Justice Sanjay Karol, Judge, Supreme Court of India.

An esteemed panel of speakers contributed valuable perspectives:

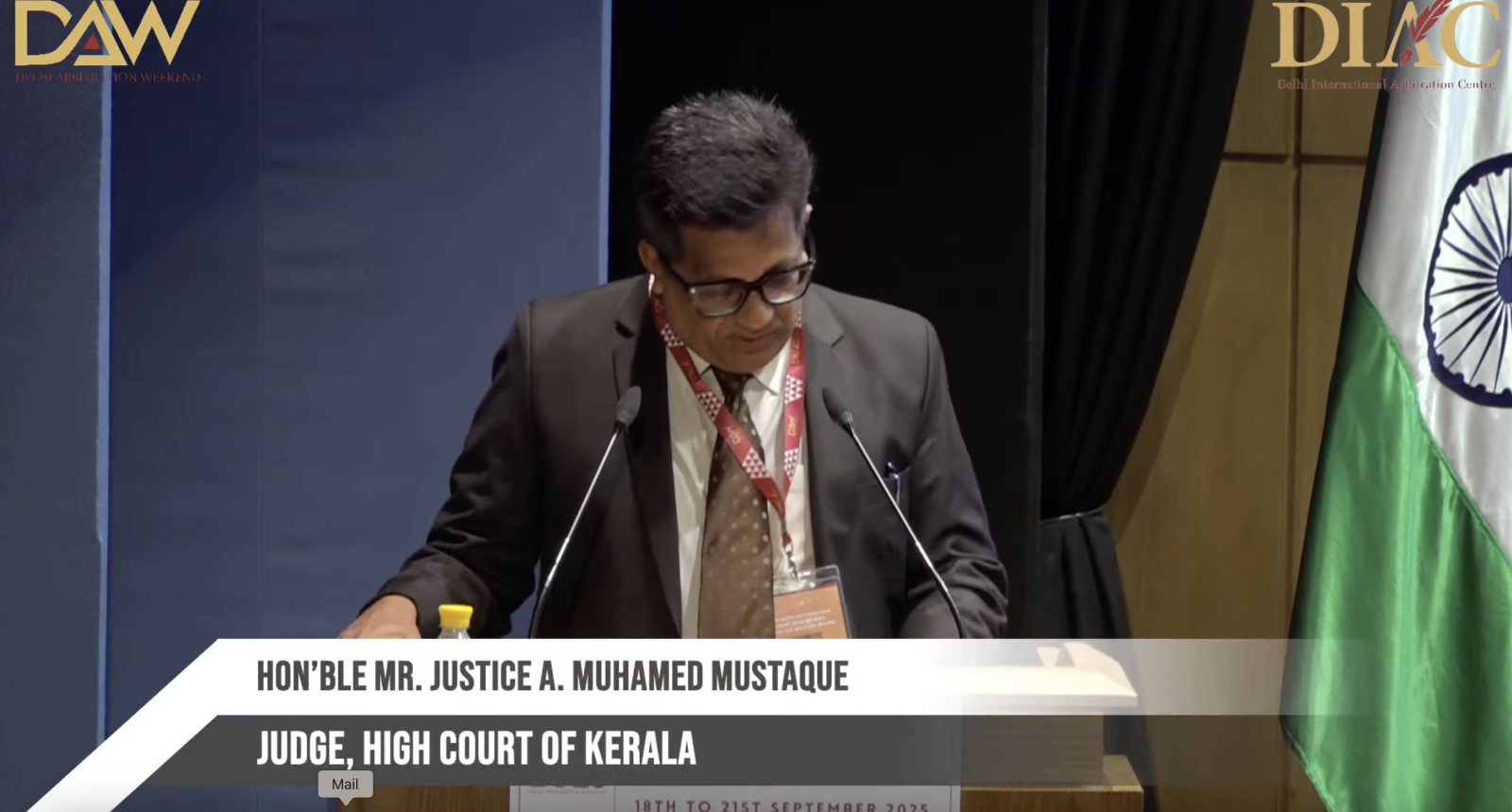

- Mr. Justice A. Muhamed Mustaque, Judge, High Court of Kerala

- Mr. Pramod Nair, Senior Advocate

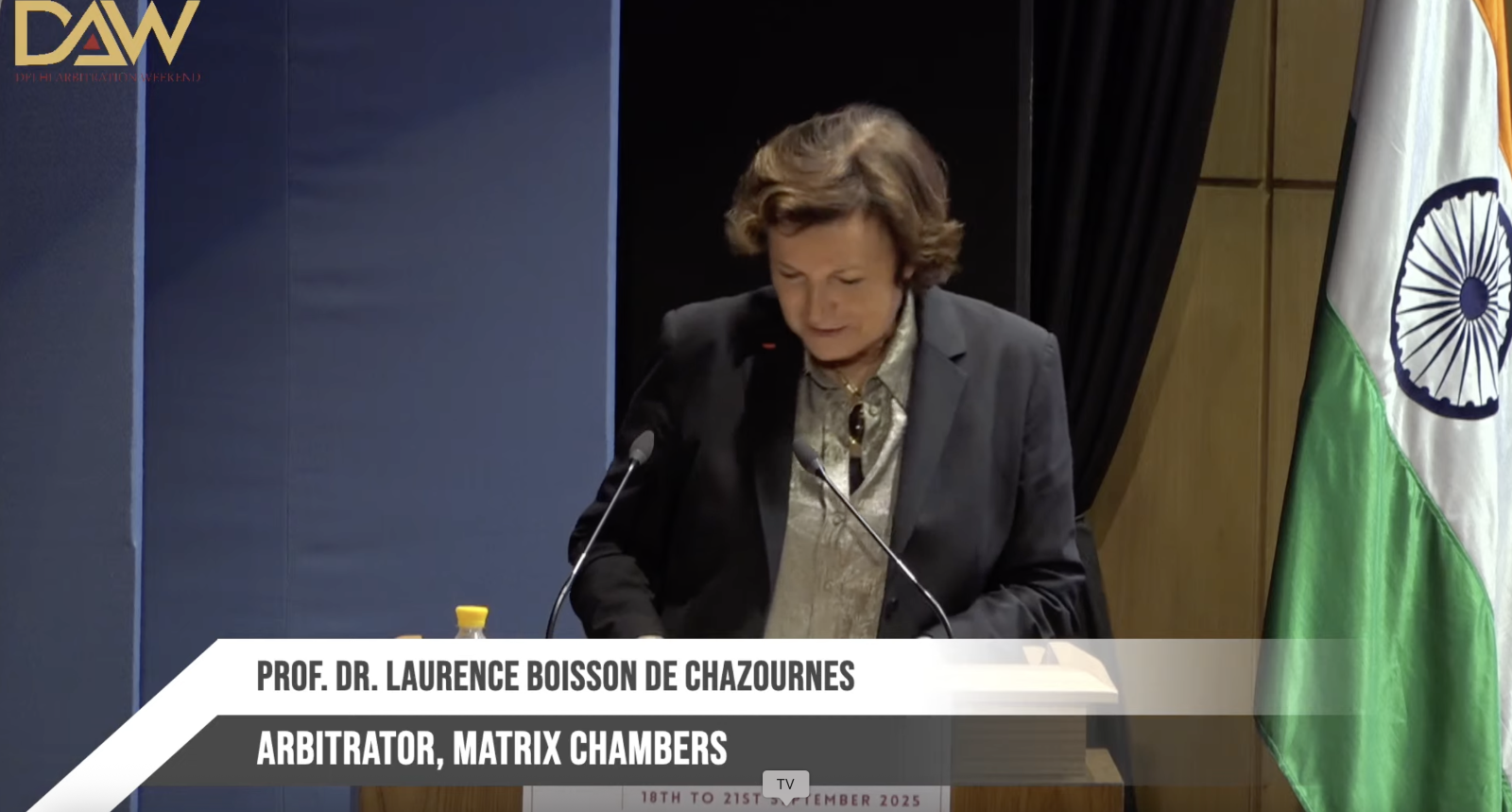

- Prof. Dr. Laurence Boisson de Chazournes, Arbitrator, Matrix Chambers

-

Prof. Joongi Kim, Professor of Law, Yonsei Law School.

Justice Sanjay Karol opened the session with a warm and gracious welcome, extending heartfelt greetings to those present both on and off the dais. Justice Karol humbly positioned himself not as a judge but as a student of investment arbitration, expressing his intent to share his thoughts freely and candidly. He commended the efforts behind Delhi Arbitration Week 2025, which by its sixth day had successfully hosted 27 sessions with 135 distinguished speakers.

Speaking on the theme “Investment Arbitration at a Crossroads: Key Developments, Emerging Trends and Future Directions,” Justice Karol contextualized the topic within the broader framework of global uncertainty — social, economic, and political. He traced the tension between the rule of law and rule by law, underscoring the way political structures influence the legal frameworks that govern foreign investments.

Justice Karol provided a comparative view of other jurisdictions. He discussed the UNCITRAL Model Law and the influence of other legislative templates, such as the English Arbitration Act, on shaping global arbitration regimes. He gave particular attention to UAE’s dual-track system, highlighting how offshore courts like the DIFC and ADGM have created special zones with incentives for foreign investors, akin to India’s SEZs.

Transitioning to the history and evolution of investment arbitration, Justice Karol traced its roots to the post-World War II period, when bilateral investment treaties (BITs) emerged to balance the competing interests of investor protection and state sovereignty. He noted that Germany and Pakistan signed the first BIT in 1959, marking the beginning of a wave of treaties that surged in the decades that followed.

In the Indian context, he discussed the new Model BIT, which introduced stricter definitions of investment, narrowed fair and equitable treatment standards, and imposed a requirement to exhaust domestic remedies for five years before initiating arbitration. Despite its cautious approach, only a few countries have signed on to this model, leaving India at an inflection point.

In concluding his address, Justice Karol underscored the need for clarity and balance in future treaty drafting, ensuring states retain regulatory autonomy while investors receive effective remedies. He urged that investment arbitration not be viewed as a zero-sum game, but rather as a platform for mutual trust and cooperation.

Drawing from judicial wisdom, he reminded the audience that justice must not only be done but must also be seen to be done. Echoing this principle, he called for treaties, contracts, and arbitration agreements to be comprehensive and forward-looking, accounting for all reasonably foreseeable contingencies.

Justice A. Muhamed Mustaque delivered a compelling and thought-provoking address, combining personal anecdotes, judicial experience, and a forward-looking vision for the role of technology in investment arbitration and dispute resolution.

Justice Mustaque chose to speak on the use of technology in Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS), drawing upon his extensive experience as the Chairman of the Computerization Committee of the High Court of Kerala, a position he has held for five years. He offered candid reflections on India’s journey toward judicial digital transformation, acknowledging the sincere efforts but also highlighting the structural limitations and philosophical misalignments that have hindered meaningful progress.

He noted that despite nearly two decades of attempting digital reform, Indian courts still struggle to transition fully into a technology-integrated system. In comparison, countries like the UK, which began reforms only in 2016, have often outpaced India in implementation. He argued that the core issue lies not in software or judicial resistance, but in trying to apply rules built for physical courts to digital platforms, without rethinking the architecture of the system itself.

Justice Mustaque extended this philosophical lens to investment arbitration, urging a fundamental rethinking of rules and processes in the digital era. Just as the New York Convention and UNCITRAL Model Law were defining moments in the evolution of global arbitration, he called for the development of new frameworks tailored specifically to technology-driven investment disputes, particularly in ISDS.

Addressing the current legitimacy crisis in ISDS, he pointed to concerns such as:

- Inconsistencies in rulings,

- Time-consuming and expensive procedures,

- Lack of transparency, and

-

Conflict of interest, including situations where arbitrators act as counsel in related matters.

He emphasised that while AI and algorithmic tools offer support, they cannot replace human conscience and judicial discretion. He advocated for the use of supervised algorithmic models, particularly in procedural areas such as timeline fixing, case prediction, and evidence management.

Further, he identified privacy concerns, especially under the EU’s robust data protection regime, as key challenges in adopting digital tools. Referencing examples such as the COMPAS algorithm used in the U.S. justice system, he cautioned against biases in AI and the “black box” nature of many algorithmic decisions, which may perpetuate rather than solve systemic issues.

Mr. Pramod Nair delivered a detailed and incisive presentation on the theme “Investment Treaty Arbitration and State Courts”, an area of growing relevance in the Indian and international legal landscape. He noted that despite India’s ongoing efforts to terminate or renegotiate several bilateral investment treaties (BITs), Indian courts continue to play an increasingly important role in Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) matters.

Citing India’s new BIT with Israel, Mr. Nair suggested this may serve as a template for India’s future treaties, and reaffirmed that courts will remain key actors in the evolving investment arbitration regime.

Scope of Court Involvement in ISDS

Mr. Nair outlined four broad contexts in which domestic courts, particularly in India, interact with investment arbitration:

- Enforcement of Awards

- Annulment of Non-ICSID Awards

- Interim Measures in Support of Arbitration

-

International Responsibility of States due to Court Delays or Decisions

1. Enforcement of Awards: ICSID vs Non-ICSID Distinction

He began by explaining the fundamental distinction between ICSID and non-ICSID awards and noted that India is not a signatory to the ICSID Convention, primarily to preserve the judiciary’s role in reviewing arbitral decisions, a position rooted in India’s concerns about outsourcing final adjudication to an international body.

2. Annulment of Non-ICSID Awards

Mr. Nair briefly discussed how courts in non-ICSID jurisdictions retain powers to annul or refuse recognition of ISDS awards under their domestic legal regimes. He highlighted how this broader scope for judicial review reflects a deliberate policy choice by countries like India.

3. Courts and Interim Measures

Domestic courts may also be asked to support ISDS arbitrations by issuing interim relief, such as injunctions or orders of protection. Mr. Nair outlined several reasons for this:

- Delays in Tribunal Constitution

- Relief Against Third Parties

-

Enforcement Powers

4. State Responsibility for Judicial Conduct

Mr. Nair addressed the topic of whether actions or inaction by domestic courts can give rise to state responsibility under international law. He clarified that:

From an international law perspective, all branches of the state — including the judiciary — are organs of the state. Judicial conduct can therefore engage the state’s international responsibility.

He cited several examples where denial of justice, delays, arbitrary decisions, or manifestly corrupt rulings by courts have triggered treaty claims.

Mr. Nair concluded by reaffirming the increasingly significant role of state courts in both procedural and substantive aspects of investment treaty arbitration. Whether in granting interim measures, enforcing or annulling awards, or inadvertently triggering claims of denial of justice, judiciaries are central to the future of ISDS.

Prof. Dr. Laurence Boisson de Chazournes delivered a thoughtful and timely address on the critical interface between climate change and investment law, offering a holistic and forward-looking perspective. Speaking in the late afternoon session, she began by expressing her gratitude to the organizers, the judges, and her former students in Delhi, particularly Mr. Garv Malhotra and Mr. Arijit Sanyas, for their warm welcome and support.

Professor Boisson de Chazournes opened her remarks by emphasising that climate change is not solely an environmental issue. It is also a social, cultural, and economic challenge. This broader framing set the stage for her argument that international investment law has an important role to play in addressing the economic dimensions of the climate crisis.

She identified the global reliance on fossil fuels as a central problem and stressed the urgent need to transition toward renewable energy and sustainable consumption patterns. In this context, she underlined that trade and investment are not obstacles, but rather key instruments that can facilitate systemic change.

Professor Boisson de Chazournes urged a shift in narrative, from viewing climate change and investment law in opposition, to seeing their interplay and mutual reinforcement. She argued that investment law must evolve to accommodate the imperatives of climate action, and that regulatory measures taken by states to meet their climate obligations should not be presumed to violate investor protections.

She then discussed three key interfaces where this interplay is most pronounced:

- The Right to Regulate

- Fair and Equitable Treatment (FET)

-

Enforcement of Awards and Public Policy

“Climate change is an existential problem of planetary proportions that endangers all forms of life and the very health of our planet.”

She suggested that this powerful framing may influence national courts to deny enforcement of awards that conflict with climate-related public policy, especially in jurisdictions that recognise such defenses under the New York Convention or domestic arbitration laws.

Prof. Boisson de Chazournes concluded with several key reflections:

- Arbitrators and judges will increasingly encounter arguments grounded in the ICJ’s advisory opinion, and must engage with them thoughtfully.

- The advisory opinion promotes a holistic application of international law, emphasizing cooperation and coherence between regimes.

-

As states begin to adopt more stringent climate measures, tensions with trade and investment regimes may grow, but she maintained that there is legal space to reconcile these objectives, especially by interpreting standards like proportionality and necessity in light of climate goals.

She encouraged careful, case-by-case adjudication, recognizing the complexity of aligning investment protections with urgent climate imperatives.

Prof. Joongi Kim delivered a compelling and nuanced address on the annulment regime in investment treaty arbitration, weaving together doctrinal insight, procedural complexity, and practical implications. His presentation, structured around a comparative analysis of ICSID and non-ICSID annulment frameworks, was made especially engaging by his opening with a well-known Chinese parable that emphasized the unpredictability of outcomes, a metaphor that recurred throughout his discussion of jurisdictional challenges and forum selection.

Prof. Kim began with a traditional Chinese story about an old man and his horse — a parable about fortune, misfortune, and perspective, suggesting that we often don’t know whether something is truly good or bad at the moment it occurs. This parable served as a thematic anchor for his legal analysis, particularly as he examined how seemingly unfavourable developments in arbitration (such as the choice of seat) can sometimes yield unexpected benefits.

Prof. Kim outlined the two principal regimes for investment arbitration annulment:

1. ICSID Annulment Regime

- Governed entirely by the ICSID Convention — a self-contained and autonomous legal system.

- Annulment Committees are appointed by ICSID; parties have no influence over the appointment.

- No appeals or judicial reviews in national courts.

- Grounds for annulment are narrow and exclusive, with five primary grounds, notably:

- Tribunal manifestly exceeded its powers

- Serious departure from a fundamental rule of procedure

-

Failure to state reasons in the award

2. Non-ICSID Annulment Regime

- Involves national courts at the seat of arbitration, guided by domestic arbitration laws.

- Unlike ICSID, multiple levels of appeal may be available.

- Annulment standards vary significantly across jurisdictions, and may include:

- Public policy violations

- Breach of natural justice

- Allegations of corruption or fraud

-

Deference to tribunal decisions differs: some courts adopt a de novo review (especially for jurisdiction), while others defer more heavily to arbitral findings.

Prof. Kim concluded with practical reflections:

- Investors confident in their merits may prefer ICSID for its finality and predictability.

- States may favour non-ICSID forums where local courts can review awards, potentially offering more avenues for challenge.

-

The choice of counsel may influence seat determination inadvertently, choosing local counsel could lead to selection of their jurisdiction as the seat.

Session 4 brought together distinguished legal minds to explore the complex intersection of climate change, investment arbitration, and annulment regimes.

As Day 2 of DAW 2 came to a close, it reflected on a day marked by depth, diversity, and dialogue. From the evolving interplay between investment law and climate change, to the strategic considerations surrounding annulment in international arbitration, today’s sessions offered powerful insights and important provocations.