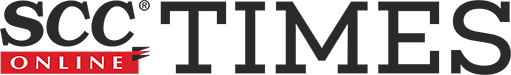

On 21-09-2025, the Delhi International Arbitration Centre (‘DIAC’) conducted the last day of the 3rd Edition of the Delhi Arbitration Weekend (‘DAW 2025’) with the last session and a closing ceremony. The event was graced by Justice Surya Kant, Judge, Supreme Court of India; Justice Ujjal Bhuyan, Judge, Supreme Court of India; Shri Arjun Ram Meghwal, Ministry of State and Ministry of Law and Justice; Justice Devendra Kumar Upadhyaya, Chief Justice, Delhi High Court; Ms. Anju Rathi Rana, Law Secretary, and other dignitaries.

SESSION 5 | Drafting of Enforceable Awards: International Best Practices

Hosted by the Supreme Court, Delhi High Court, and DIAC, the session what goes into making an enforceable award and the international best practices for it.

Chaired by Justice Ujjal Bhuyan, Judge, Supreme Court of India, the esteemed panel comprised of Justice Shekhar B. Saraf, Judge, Allahabad High Court; Mr. Siraj Omar SC, Founding Director, Siraj Omar LLC; Mr. Gourab Banerji, Senior Advocate; and Dr. Jane Willems, Arbitrator.

Kicking off the last panel discussion of DAW 2025, Justice Ujjal Bhuyan delivered an introductory speech. After providing a brief explanation of arbitration and its necessity, he explained the meaning and purpose of an arbitral award, stating that an award must not only declare a winner but also specify the remedies in enforceable terms, such as mandatory amounts, timelines, or obligations.

“The arbitral tribunal has a duty to make every effort to draft an award that will withstand judicial scrutiny, even though limited, and enforcement proceedings.”

– Justice Ujjal Bhuyan, Judge, Supreme Court of India

Coming to enforceability, Justice Bhuyan underscored that the utility of an adjudicatory process rested not only on fairness and speed, but also on whether that decision can be recognized and enforced by the Courts. In his opinion, the essentials of an enforceable award are that it must conclusively resolve the dispute, comply with the substantive law concerned, provide the reasoning for the decision, and be the result of a process that treats both parties equally, satisfies procedural fairness, and follows due process.

“An award is more than a technical decision. It is the story of the parties, their dispute, and the resolution of the dispute by the arbitral tribunal.”

– Justice Ujjal Bhuyan, Judge, Supreme Court of India

Furthermore, he elaborated on the structural aspects of an award, such as clarity, coherence, use of simple language, not to mention culturally specific references, which may be suggestive of bias, being well structured, etc. He highlighted the three parts of a well-structured award, i.e., the beginning introduces the nature of the dispute, the parties and the relationship, the arbitration agreement, procedural history, issues for determination, and the applicable law. The middle is the analytical core wherein the tribunal examines each issue, reviews the submissions, evaluates the evidence, interprets the contract, and applies the law. Finally, it concludes with the dispositive section, which contains the binding order that resolves the dispute by translating legal analysis into enforceable directions.

“What is of crucial importance is that the dispositive portion should be clear and unconditional. Conditional language, such as unless or on condition that, undermines finalities and therefore should be avoided.”

– Justice Ujjal Bhuyan, Judge, Supreme Court of India

Drawing upon the history of arbitration law in India, Justice Bhuyan underscored how most arbitral awards ended up in the Court due to challenge under Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (‘the Act’), and thus suffered from enforceability issues. In this regard, he also spoke about the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, 1958 (‘New York Convention’), which is a multilateral treaty mandating that Courts in the contracting states shall recognize and enforce arbitral awards passed in other contracting states. He mentioned that a pivotal feature of the New York Convention was its provision of a limited but exhaustive list of grounds on which recognition and enforcement of an award may be refused. These grounds are procedural in nature, intended to safeguard fairness and due process, and do not allow re-examination of the decision on merit.

Lastly, Justice Bhuyan emphasized that the key to enforceability was practicing restraint in challenging awards, i.e., allowing arbitration to come to its logical conclusion with the bare minimum, if not total, judicial intervention.

Taking the discussion further, Mr. Gourab Banerji began his speech by commending the Delhi High Court and DIAC for appointing younger members of the bar to deliver enforceable awards. He elaborated upon a few essential elements of drafting an enforceable award from the Indian perspective, which were as follows:

-

Introduction: This part mentions the parties, the representatives, the Arbitrators, and a declaration of independence of the Arbitrator(s).

-

Arbitration Agreement: This part mentions the original contract, the arbitration agreement, the seat, the rules, and the language.

-

Procedural History: He emphasized that this aspect was important as there was procedural paranoia and the arbitrator had to demonstrate that they upheld natural justice and gave the parties a choice, particularly in an ex parte award.

-

Factual background and cause of action

-

Summarizing the party’s contentions: He underscored that this aspect was very contentious, as some new arguments would sneak in through written submissions that were not argued. Thus, the arbitrator had to ensure that every argument was dealt with.

-

Analyzing the issues: Regarding this aspect, Mr. Banerji criticized the Goldman formula wherein the arbitrator decided all the points that arose from the pleadings. He underscored the importance of the application of mind, framing of the issues, and framing the points of dispute, and then analyzing, discussing, and giving reasons.

-

Operative or dispositive segment: He highlighted that the most important portion was the decision, and the arbitrator should mention the costs and interests in the calculation.

-

Signature of the parties and arbitrator(s).

Adding the international perspective to the conversation, Dr. Jane Williems mentioned the three essential elements of an enforceable award in international commercial arbitration, which are as follows:

-

Opportunity to be heard: Dr. Willems underscored that the arbitrator/tribunal shall ensure that the parties had a reasonable opportunity to be heard and the arbitral award should reflect that these requirements were met, both from procedural and substantive perspectives. This includes recalling the procedural history at length from the initiation of the arbitration to the rendering of the final award. The reason for mentioning the procedural history was to ensure that the parties, the institution, the reader, and the enforcing or appellate Courts were satisfied that due process requirements were met. She added that the substantive matter should also be mentioned in detail, i.e., each party’s case, identified issues, disputed facts concerned, and submissions.

-

Reasoning: She emphasized that reasoning was the core element of the award, as it contained the thought process underlying the decision of the arbitrator. Beginning with the disputed facts, the arbitrator should provide the relevant legal authority and explain how the decision was made by applying the law to the facts to reach a clear conclusion.

-

Cost-efficient determination of the dispute: Dr. Willems highlighted that the third important element was the prompt delivery of an arbitral award because delays and challenges cost money. The Arbitrator should give some deadlines to the parties as to when the final decision should be expected. Furthermore, she stated that the writing process of the non-substantive part should begin in advance, not after the receipt of the post-hearing submissions.

Thereafter, Mr. Siraj Omar SC provided his insights from the Singaporean perspective, wherein he explained why it is important to draft an enforceable arbitration award. He remarked that arbitration was a journey wherein the arbitration clause was the start and a final, binding, and enforceable award was the ultimate destination. Parties are not interested in the journey, but they want to get to the destination safely. The resolution of that dispute is ultimately manifested in the award. If that award is not enforceable, then it is a worthless piece of paper, and the Arbitrator or the Tribunal has failed.

Mr. Omar cited three cases to explain the issues that arose and why the award was unenforceable:

-

Wan Sern Metal Industries Pte Ltd v. Hua Tian Engineering Pte Ltd: In a construction dispute, the Arbitrator had dismissed the claimant’s claims and allowed most of the respondent’s counterclaims, so the claimant challenged the award. The Court set aside the award in respect of one part of the respondent’s claim, holding that the Arbitrator had breached principles of natural justice by failing to apply her mind to the party’s cases in respect of one issue. The Arbitrator had oversimplified and overlooked some parts of the respondent’s case on that issue. Citing this case, Mr. Siraj explained that the Arbitrator needs to be thorough, carefully understand the cases and arguments, analyze each aspect of the cases, and make sure that the analysis was reflected in the award. Hence, it was essential to mention the reasoning.

-

DOM and DON: In this case, the claimant applied to set aside the award relating to consultants’ fees that the respondent had been granted. The Tribunal had found insufficient evidence to justify the $2 million claim but still awarded 50% of the claim fees after applying a “discount” for the consultant’s fees without analysis as to how this figure was arrived at. The claimant argued that the parties did not have a chance to address the Tribunal’s chosen method of valuation, the valuation of the consultants’ fees, and that they could not foresee this outcome. The Court held that there was no basis for the Tribunal’s findings, and neither of the parties had the opportunity of addressing it. Mr. Siraj concluded that this case illustrated that, unlike tribunals, Courts had broad statutory and inherent powers to do justice. Tribunals cannot make findings other than based on the arguments and evidence presented to them by the parties.

-

DJO and DJP: The award-debtor claimant filed an appeal to set aside the award because the Tribunal had copied substantial parts of the award from awards in parallel arbitrations involving similar facts and similar underlying contracts. The Court set aside the award, holding that the Tribunal had failed to address its mind to the facts and arguments. Citing this case, Mr. Siraj highlighted that an arbitrator may be adjudicating similar proceedings, but an Arbitrator had to unilaterally decide a case on its own merits without being influenced.

In conclusion, Mr. Siraj underscored that an enforceable award rested on three essentials- respect for the jurisdiction, observance of due process, and clarity in reasoning and remedies.

“Credibility of arbitration depends less on winning arguments and more on delivering awards that are capable of surviving scrutiny across borders.”

-Mr. Siraj Omar SC, Founding Director, Siraj Omar LLC

The last speaker, Justice Shekhar B. Saraf, began his presentation by remarking that at first glance, the issue of non-enforcement may appear to stem nearly from judicial intervention. He stated that since the award emerges from a private process that ultimately requires enforcement by the Court, it was justified that Courts exercised prudence in reviewing such awards, whether it be at the stage of setting aside of an award or at the stage of enforcing an award.

“The risk of non-enforcement arises not from judicial skepticism alone, but often from inherent defects in the award itself that unfortunately prevent enforcing courts from executing it as a decree.”

-Justice Shekhar B. Saraf, Judge, Allahabad High Court

Justice Saraf proceeded to cite cases to highlight issues that had come up over the past years in the enforcement of awards. In National Oilwell Varco Norway AS v. Keppel FELS Ltd.1, the Court refused enforcement of an award on the ground that it had been rendered in favor of a non-existent entity. The Court observed that the arbitration itself was functional as proceedings commenced against or in favor of a non-existent legal person and held that such cannot give rise to a valid award unless the naming can be treated as a misnomer.

In DJP v. DJO, the Apex Court of Singapore upheld the High Court’s decision to set aside an arbitral award on the ground that the Tribunal had breached the rules of natural justice by extensively copying a portion of its award from other arbitral awards. The award also contained errors, including reference to unsighted authorities, incorrect application of formulae, and reliance on the wrong law of the seat of arbitration for interest and costs. The Court also emphasized that Arbitrators must avoid relying on materials not equally accessible to all parties or co-arbitrators.

He cited another example of Satluj Jal Vidyut Nigam Ltd. v. Jaiprakash Hyundai Consortium, 2023 SCC OnLine Del 4039, wherein the Court set aside an arbitral award on the ground that the Tribunal had entertained financial claims premised on speculative mathematical derivations without any foundation in the pleadings or cogent evidence.

Referring to these cases, Justice Saraf provided a few suggestions:

-

In case there is a jurisdictional challenge, preferably, that should be adjudicated before substantive determination on the merits.

-

The question of liability should be addressed before the assessment of the quantum.

-

Any preliminary issue should be resolved before related or dependent matters to ensure the enforcement of awards.

-

References and precedents cited in the award are correct, and the citations are cross-verified.

Lastly, regarding the use of AI, he remarked that though it could be used by the Arbitrators to make their job easier, it should not be a substitute for carrying out analysis. In case AI conducts it, it should be critically reviewed, independently verified, and corrected before inclusion in the final award.

Thus, the discussion concluded with a question-and-answer session with the audience.

|CLOSING CEREMONY|

Bringing the event to a close, the closing ceremony was graced by Justice Surya Kant, Judge, Supreme Court; Shri Arjun Ram Meghwal, Minister of State, Ministry of Law and Justice; Mr. Gary Bonn, Chair of the International Arbitration Practice Group, Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr LLP; Justice Devendra Kumar Upadhyaya, Chief Justice, Delhi High Court; and Justice Subramonium Prasad, Judge, Delhi High Court.

The ceremony began with a soulful performance by Padmashri Pandit Madhup Mudgal.

Keynote Address:

Mr. Gary Bonn began his keynote address by explaining the meaning behind the painting named ‘Peace and Justice’ depicted in the main courtroom of the International Court of Justice. Thereafter, he traced the history of arbitration from the Mesopotamian civilization to anticipations about the future.

-

2600 BC: A fragment of a ‘Stele of the Vultures’ (ancient Mesopotamian stone monument) mentioned the resolution of a border dispute between two states by the king of the third state. It depicted the king marking the border, i.e., where he had arbitrated the dispute after being chosen by the two warring States.

-

3500 BC: A cuneiform tablet depicted the first known arbitral award on a water dispute.

-

300 BC: The Ancient Greeks resolved their disputes in ordinary matters or state-to-state disputes via arbitration, as depicted through an excerpt from a treaty between Athens and Sparta.

-

1516: A treaty was signed between King Francis I of France and the Swiss Confederation, bringing peace between them as they agreed to resolve future disputes by two Arbitrators chosen by the parties, along with the fifth decisive voice chosen by those four.

-

1622: The Lex Mercatoria defined arbitration, arbitrators, award, and the concept of impartiality of an arbitrator.

-

1680: The first known example of arbitration was when two parties, in the United States, decided that two Arbitrators would be appointed to decide their dispute, and in case they couldn’t agree, a third person would be appointed as an umpire to make a final decision.

-

1751: The New York Weekly Post Boy mentioned a letter to the editor wherein the editor described that if the sender didn’t accept his counterparty’s offer to arbitrate, then they would be stuck in expensive litigation for years.

-

1959: A New York case stated that the previous treatment of an arbitral award in America was a dark chapter, as there was a precedent holding arbitration agreements as unenforceable because they were based on mutual trust.

He further illustrated the history of arbitration, which became more acceptable as a mode of dispute resolution, especially international disputes, resulting in the New York Convention, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes Convention, 1965, the UNCITRAL Model Law on Commercial Arbitration, Bilateral Investment Treaties with arbitration clauses, the establishment of arbitral institutions, etc. Eventually, international arbitration became common, as simple merchants, big companies, and organizations all opted for arbitration.

Lastly, Mr. Bonn elaborated on the six Es of arbitration, namely, efficient, expeditious, even-handed, enforceable, and electronic. Regarding the future, he remarked that Arbitration was part of a choice that arose from the freedom to choose in a democratic society; thus, he opined that the rule of law and freedom to choose would continue.

Presidential Address:

At the outset, Shri Arjun Ram Meghwal expressed that there was a need to revisit Section 34 of the Act and asked the audience whether their deliberations over the course of DAW 2025 had resulted in this realization too.

While underscoring the importance of the Act and the Commercial Courts Act, 2015, he assured that the Mediation Act, 2023, was still in the works and would soon bear fruit. Additionally, he stated that the India International Arbitration Centre Act, 2019, needed more work.

Shri Meghwal remarked that Mission Viksit Bharat 2047 would be successful if the economy kept growing, for which, disputes needed to be resolved quickly and properly. The swift resolution of disputes through ADR would increase trade, entrepreneurship, and industries, and India could grow beyond the title of the fourth-largest economy in the world. In his opinion, this required reforms and the adoption of international best practices of arbitration.

Lastly, he requested the esteemed audience comprising judges, advocates, and experts to suggest the changes and amendments that were required in India’s ADR laws, which he would support and platform or raise before the correct authority.

Valedictory Address:

Justice Surya Kant, in his insightful address, commended the Delhi High Court, DIAC, the audience, participants, and guests for engaging with evolving doctrinal debates and practical questions of arbitral practices over the course of DAW 2025.

From the judicial lens, he provided his insights on the concept of independence and integrity of an arbitrator. He stated that arbitration, which was once a niche mechanism, had become the backbone of commercial dispute resolution. Although arbitration promises efficiency, expertise, and finality, in his opinion, its legitimacy rests on two essential pillars, namely independence and integrity. These pillars were reflected in both Indian and International Law.

“While independence ensures freedom from influence, integrity assures fairness, transparency, and the confidence of the parties. Without these pillars, arbitration is reduced to a hollow ritual, and it is here that the judiciary assumes its quiet but vital role.”

– Justice Surya Kant, Judge, Supreme Court

Justice Kant remarked that with such a clear architecture, the real question lay in how Courts interpreted and enforced these safeguards of the two pillars. In this regard, he stated that the Indian courts had gone the extra mile by enriching and deepening the meaning of these safeguards. The Indian Courts also emphasized strengthening other fundamental features of arbitration and, most notably, the principle of party autonomy. The Supreme Court made it clear that while arbitral autonomy must be respected, the judiciary could not abdicate its supervisory role where natural justice was at risk.

Underscoring the growth of Indian jurisprudence, Justice Kant addressed the remaining contemporary challenges, such as delay, quality, consistency, and enforcement.

“Even if the judiciary takes strides towards a pro-arbitration stance and champions minimal intervention. Such efforts will seem futile unless other stakeholders also accept accountability and responsibility in their actions.”

– Justice Surya Kant, Judge, Supreme Court

He commented that it was vital for Arbitrators and the legal fraternity to pause and reflect on what arbitration truly stands for and the objective it is meant to achieve. Thus, the legal practitioners must resist that instinct to litigate, and Arbitrators must also guard against extending timelines, multiplying procedure hurdles, or postponing awards without compelling cause. He remarked that arbitration is designed to be efficient, fair, and final, but when it begins to mimic the worst excesses of litigation, it risks losing its very purpose.

“Too often we approach it through the lens of conventional litigation, where every stage becomes an opportunity for challenge and where delay is treated almost as a strategy.”

– Justice Surya Kant, Judge, Supreme Court

In conclusion, Justice Kant expressed his optimism with the hope that the fraternity would move, not towards more intervention, but towards more discipline. Not towards more rules, but towards stronger institutions and deep trust so that justice is not just done but truly seems to have been done.

“Justice, after all, forms the very basis of the state and remains the surest bond that holds together all human commerce.”

– Justice Surya Kant, Judge, Supreme Court

Closing Remarks:

Ending the eventful 3rd Edition of DAW, Justice Subramonium Prasad illustrated how remarkable the event had been with an increase in participation of international institutions from 9 to 16 and external events from 6 to 22.

Furthermore, he stated that India stood at a pivotal juncture of the arbitration journey, as over the past decade, there had been significant reforms, institutional strengthening, and a growing trust among global stakeholders in this arbitration framework.

“The Delhi Arbitration Weekend 2025 serves as a powerful reformation of this transformative progress, highlighting India’s readiness and determination to embrace and implement global best practices while addressing its unique socio-legal context.”

– Justice Subramonium Prasad, Judge, Delhi High Court

Thereafter, Justice Prasad expressed his deep gratitude towards the Patron-in-Chief, Justice B.R. Gavai, Chief Justice of India, for his steadfast support and invaluable leadership, Justice Kant for his guidance, and Justice Upadhyaya for being the strongest pillar of support. He also thanked Shri Arjun Ram Meghwal and Justice Stephen Gageler, Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, for their presence.

Furthermore, commending Mr. Bonn for his keynote address, he proceeded to thank his brother Judges, namely, Justice Sanjay Narula, Justice Teja Karia, and Justice Sachin Dutta. He also thanked the various DIAC and DAW teams and coordinators, including the Registrar General and judicial officers, for their indispensable hard work and support.

Justice Prasad extended his heartfelt gratitude to Justice Vibhu Bhakru, Chief Justice, Karnataka High Court, who sowed the seeds for DAW, and Justice Rekha Palli, Former Judge, Delhi High Court, for providing the statement of purpose for the event, thus creating its backbone.

Lastly, he thanked the speakers for their invaluable insights, the delegates for their presence, and the academic partners, sponsors, and institutional supporters for their partnership.

With this, the remarkable 3rd edition of the Delhi Arbitration Weekend ended with a hope that the conversations, collaborations, and commitments would carry on.

1. [2021] SGHC 124